Living Abroad Changed Me as a Person

Maybe you can never go home again, as the person you were

Departure

I was nineteen years old the first time I left my country to live in another. I left the hills of rural New England behind to spend a year of my college studies in the fuming urban swirl of Madrid. Before I arrived, I had only the vaguest idea of what life in Spain was like (this was before the Internet, if you can imagine such a thing). When I arrived and saw the fleets of white taxis wearing their red sashes and circulating like courtiers up and down grandiose boulevards with fountains, esplanades, and stone buildings bedecked with orgiastic allegories of Art and Victory, I was speechless. Sitting in a cafe furnished in marble and mirrors and drinking a steaming café con leche, I thought, “This is the life I want.”

I decided then that I wanted to become a European. There was something so compelling about the way of life I was discovering that I knew I wanted to continue to immerse myself in it. Over the years that followed, the road to becoming a European turned out to be a circuitous one with terrible traffic and plenty of tolls, but in the end, I reached my goal. Today I have a US passport and a European one, and have lived on this side of the Pond for over twenty years.

And, interestingly, I am not the same person who climbed off the plane at Barajas all those years ago. While it is obviously true that we all change over the course of our lifetime, the experience of living abroad has changed me in fundamental ways that I would not trade for anything.

In this essay, I would like to talk about how living in other countries has changed me and others. Wanting to be sure that I was not some bizarre outlier, I interviewed several of my friends before writing this piece. What follows consists of my own observations interspersed with some of theirs. Overall, there was agreement among those I spoke to: Whether or not you want it to, living abroad changes you, in ways that are mostly—but not always—positive.1

When I was teaching at university, I often recommended that my students study or live abroad if possible, saying, “living in another country will make you a more complex and more interesting person.” But I would also insist that it should be for one year or more—anything less, and you can hold your breath and not inhale the local atmosphere. Further, the more different the new country, the bigger the opportunity for change and growth—moving from Sweden to Norway is not nearly as challenging as moving to Australia.

I have noticed that my recent essays have been stretching toward the breaking point in terms of length—and, concomitantly, the demands they make on the reader’s time. Aiming for concision, here I will condense all of my observations into only three main areas. Here is what I have arrived at: living in another culture changes you in terms of your perspectives, your sensibilities, and your development as a person. Let’s see how that happens.

Perspectives

The most obvious thing that happened when I left behind the world I knew and entered another one is that I saw that there is more than one way of doing everything. The assumptions I had about how everything worked, or had to be, were shown to be just that—assumptions, not facts. One of my informants (I am borrowing this word from linguistics, even though it can sound rather ominous to some people) said of living abroad, “I learned that there isn’t just right and wrong; there are other ways of doing it that aren’t necessarily wrong.” What seemed a dichotomy suddenly burst like a firecracker. Another spoke of learning “different ways of being in the world”. Yet another summarized it thus: “When you’re surrounded by differentness, it’s hard not to have your horizons broadened.”

Why is it so troubling—sometimes wrenching—to be confronted with differentness and to have our assumptions fall to the ground and shatter? I think that these are the pains associated with the birth of a major realization: Our very understanding of the world is conditioned by our culture.

Clifford Geertz wrote in 1973, “Culture is the fabric of meaning in terms of which human beings interpret their experience and guide their action.” In other words, culture is a lens through which we view the world. What we think of as “reality” is our perception of the world through that lens. What we believe to be right or wrong depends on the characteristics of the lens; people with a different lens will see other things as right and wrong.

When we step out from behind the lens of our own culture and peer through that of a different culture, it is disorienting and unsettling at first. Even more unsettling is when we swing this new lens around to look at our homeland. Suddenly everything is topsy-turvy and nothing is safe and “normal”. But this initial loss of stability eventually gives way to great wisdom.

Let’s make this more concrete with some examples—take housing. A major component of that which we call the “American Dream” is owning one’s own home. This is seen as a sign of having “made it” and of being inducted into the sacred Middle Class of the modern American mythos. Many Americans (outside of the major cities, at least) will insist that living in an apartment is something that may be fine for a twenty-something, but a respectable adult will own their own house. (Which, confusingly, they will call a home rather than a house.)

Imagine the shock it can produce, then, when an American arrives in Europe—virtually any country will do as an example—and sees that millions of people are quite content to live their entire lives in apartment buildings, many of them as renters! The American sees these people submit themselves to the indignation of shared walls and deny themselves the pleasure of mowing the lawn and cleaning the gutters. The American watches as these highly suspicious people leave their homes and walk to buy groceries, possibly even stopping by a café because they saw an old friend sitting there. The American may reach full-on apoplexy upon learning that many of these people do not even own a car!

This is such a shockingly different way of doing living one’s life that it can be painful to adjust to the idea that, seen through the lens of this culture, all of these things are normal. And then, to the open-minded individual, comes the inevitable question: If both of these lifestyles are normal, which one is actually better? And suddenly, here we are, forced to ask ourselves how we really want to live our lives, knowing that there is more than one option. An explosion of new perspectives results.

Another example: In Sweden, where I lived for many years, there is none (or very little) of the American obsession with “having it all”. Many, perhaps most, people seem to be quite content to have a perfectly good life. They make enough money to cover their non-exorbitant spending, do not rack up credit card debt, take reasonable holidays to nice places, maybe live in a little row-house that enables them to have red currant and gooseberry bushes, and spend most holidays at home with friends and family. Importantly, their children’s education is free, all the way through graduate school. And they know that if they become ill, they will receive medical care at no cost. They also know that when they retire, the state will provide them with a pension that will enable them to live a perfectly satisfactory, if frills-free, life. And as a result of all of this, there is not the interminable anxiety, competition, avarice, and need to impress people that seem to plague so many in my country of origin—not to mention the gnawing fears about illness and the future that make life hard to enjoy.

When I started living abroad, I was confronted with these sorts of contrasts, and a consequence, I was forced to look at my native country with a more critical eye, and at my own assumptions with skepticism. Also, as one of my informants said, “You get a different perspective on world events when you’re not in your home country,” pointing out that what is happening in the United States is not by far the worst catastrophe in the world at the moment. Distance can create perspective.

Sensibilities

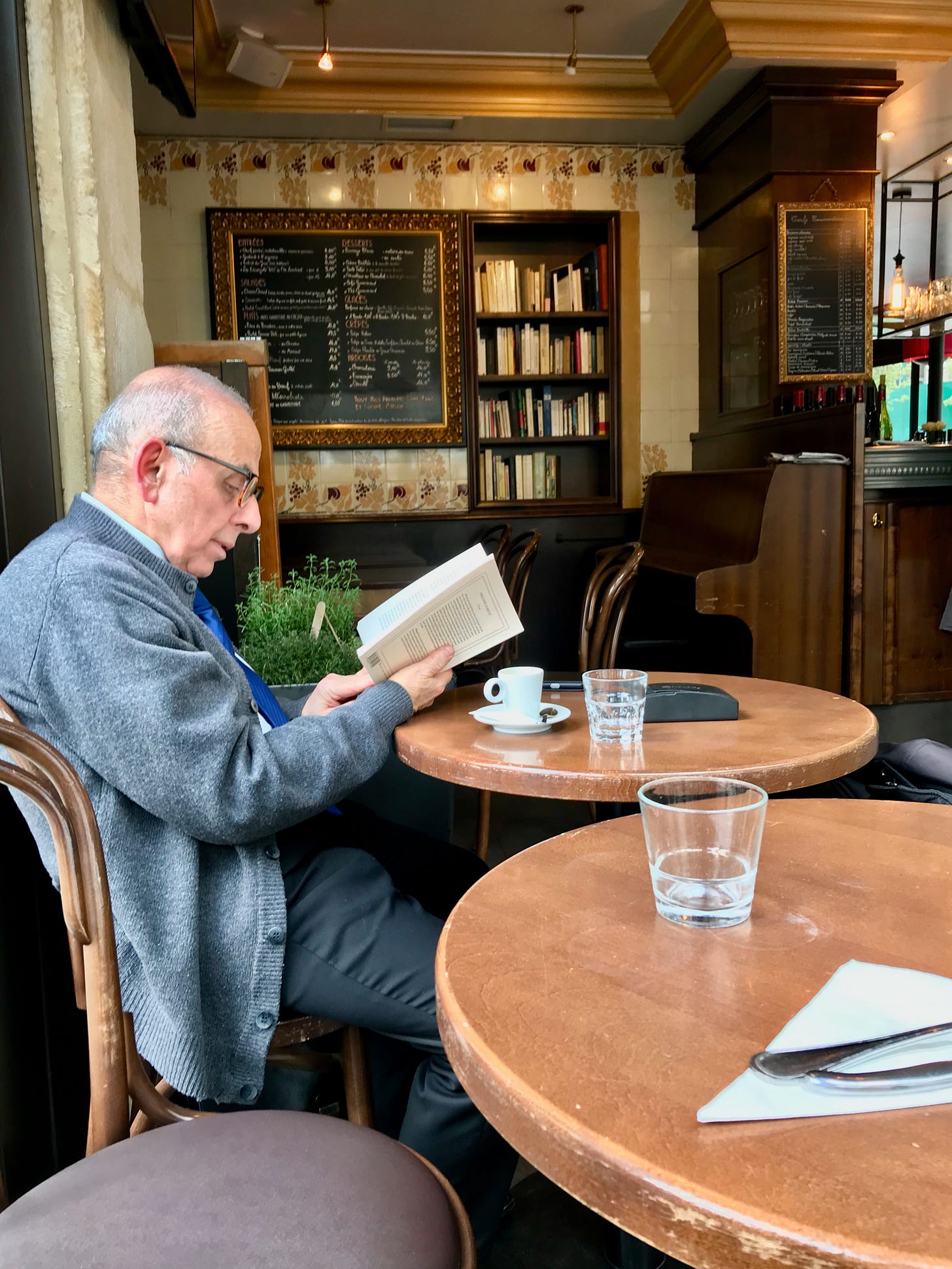

Living abroad has also changed the ways in which I respond to the world. A part of this is aesthetic. Europe in particular is a region where, at least at times, the built environment seems to have been designed to delight those in it. There is something ineffably perfect about a Parisian street, with its off-white buildings all seven stories high, crammed with shops with beautiful storefronts and cafés and restaurants with curved glass and gleaming brass, with people bustling by on the sidewalk as a few idle retirees sit on fake-wicker chairs with an apéritif and watch. For someone who grew up going to malls in the 1980s, this is appealing beyond words. I find that the greater care given to aesthetic concerns here has sharpened my own sensitivity to them.

And then there is the incredible joy I derive from the elegant shabbiness of Lisbon. I find that, once you are attuned to it, there is exquisite beauty to be found in places where you might not expect it. The other day, I fell in love with a lamppost. It had been painted green, but had faded in the sun and rain into so many different nuances of blue-green, yellow-green and gray-green that I had to stop and marvel at it for a while.

Here’s why this happens: Being surrounded by all of the strangeness that a foreign context brings makes us feel more intensely alive. The beauty of ordinary things opens up to us. When everything around you is new and different, you notice it all. And, if you are more inclined to curiosity than to fear, this can be a thrilling experience.

Nor is this limited to the physical aspects of life; the tiny events of daily life also assume grand proportions. One of my informants said, “You become grateful for more things. When I lived in Belgium, just successfully going to the store was a big deal for me.” When you are learning a language, every successful encounter is a triumph to celebrate. Yesterday I went to put gas in my car and had a very amusing exchange with the man at the cash register about the age of his clunky computer and what kind of fuel it ran on (he suggested coal). Even though I left 90 euros poorer, I felt rich and powerful.

This heightened awareness and appreciation of my surroundings has another interesting effect: it makes me more self-aware as well. Confronted with something that is new and different—whether that be a post-modern building or a dish involving cabbage—I am forced to ask myself, “What do I think of this?” The question arises over and over again: “Is this something I could like?” And because I make the choice to be open to new things, I find my range of experience expanding continuously. Who knew that I could like ice skating, or Biodanza, or white truffles? Every week, the metal shell that is the boundary of my self is hammered outward into ever larger forms.

Development

This brings us to the third and final area of change that living abroad accords us. I truly believe that I am a much more highly developed person than I would have been if I had stayed put in my native environment. The people I meet who are living or have lived abroad have a certain quality: they are multifaceted, interested, agile, unfazed—in a word, worldly. It is very difficult to live in a foreign culture for a long time without becoming more sophisticated, because so much is asked of you. The challenges of living abroad, which I have enumerated elsewhere, force us to become stronger and more resilient.

Living abroad essentially means living outside your comfort zone. Being immersed in a culture that you do not fully understand teaches you to become more comfortable with uncertainty. This, in turn, makes you more self-reliant. One of my informants said, “I’ve come to expect that I’ll get used to things. I don’t expect to fully understand everything and know everything.” Another said, “Even despite my age, I land on my feet faster than someone who has lived all their life in the same country.” Living abroad seems to teach emotional resilience and resourcefulness in much the way that martial arts training teaches physical resilience and resourcefulness.

It can also toughen the ego. One of my informants said, “If you’re totally focused on not making a fool of yourself, don’t move abroad. You aren’t going to do things right, and you can either let that bother you or laugh at it.” A sense of humor is a valuable tool in your personal toolbox if you want to make it through the frequent miscommunications, bureaucratic entanglements, and alarming disturbances that are the stuff of living in another country.

In short, living abroad forces us to grow as people. It is a challenge, like exercising a muscle, that invariably leads to the strengthening of our life muscles. Well, maybe not invariably—there are those who can’t hack it, or pick the wrong country, or change their mind, or are defeated by circumstances. As Nietzsche said, “What does not kill me, gets me permanent residency.” (Or something like that.)

The downside

You may well be thinking, “OK, this sounds wonderful, but it can’t be perfect; otherwise everyone would move abroad. So what’s the downside?” This is an eminently fair question.

As I see it, the main downside centers around loss. Let’s face it: We miss our families. But there is more to it than that. When we decide to give up the comforts of home and all of the things that are familiar to us, when we say goodbye to our friends and our loved ones, when we strike out on the lonely journey across the sea, we lose much of what we have had. Indeed, we lose a part of our identity—a part of ourselves.

One of my informants spoke at length about how moving abroad involves a weakening of connections to what was known, saying, “When you’re growing up, even if you move around a bit, you have a more local idea of yourself, and a local affinity. You root for the home sports team. You have those local connections, and you know intimately the places you come from. For me, living overseas has made that local part not exactly disappear, but diminish. Now I don’t feel rooted, really.”

Those of us who have lived in other countries for a long time often find that, talking with those back home, we have no familiarity with the television shows or cultural gossip they refer to, which feels like a loss of connection (“Breaking bad? Is that even grammatical?”). We even lose connection with who we used to be—with our previous identity. One informant said, “It’s drawn me out of the kind of person I was when I was growing up. I’ve become somebody different. In many ways, it’s changed fundamentally who I consider myself to be.” Of course, this is not necessarily a bad thing, but such a challenge to one’s sense of self does call for a ruggedness that not everyone possesses. At times it can be very painful.

On a more superficial level, living abroad can also be a blow to one’s ego. One informant said, “Living abroad has made me less of an adult. In your home country, you learn from other people and the society in general how to do the things an adult needs to do. Here I’m like, how do you do all these things?” In a sense, emigration means the death of one version of us, and the birth of another. As dramatic as this sounds, it can be a slow and painful process. We have to learn to walk again, learn to talk again, and learn to buy parking tickets using that damn machine that never seems to work.

Arrival

My personal experience is that, despite the downsides, moving abroad has been a wonderfully enriching and life-affirming experience. What is the best part of all of the change I have been forced to undergo in terms of my perspectives, sensibilities, and development? I believe it is this: Through this process, I have learned to understand myself better, have learned to identify what I truly want in life, and have learned that I do have what it takes to turn that into a reality. I feel a wonderful sense of agency as a result of the millions of experiences that have challenged me as I moved around this planet, like a beautiful stone that is polished to a shine by the rushing of years and years of water. And that stone is possibly my most valuable possession.

In the interest of transparency, one person said that he wasn’t sure how living abroad had changed him, and another argued that it’s impossible to really know, since we only live one life and thus can’t compare. All the quotes come from the other informants.

As a Brit living abroad, I'd agree with the sentiments and experiences, and maybe add a few observations.....

Walking around the food isles in a supermarket, or the local market, and reminding myself that yes, all those things that look really strange must actually be edible, and if they are there, for sale, then some people actually like eating them!

Realising that the woman ahead of me in the queue that is chatting to the teller or server, seemingly exchanging life stories, is the other side of everyone else's laid back lifestyle that I so envy and I need to relax, take another deep breath and go with the flow!

That spending two hours over a couple of coffees in a pavement cafe, without ever looking at my phone, just watching people go past, or meeting each other, or nothing much at all, is a perfectly reasonable thing to do and doesn't require me to feel guilty about wasting my time or anything at all!

That in much of Europe, someone's car is not at all connected to their status or wealth. Some of the well off businessmen, esteemed academics, respected politicians, renowned musicians or actors, will unselfconsciously drive some 20 year old heap of shit that must still pass the strict European road safety laws, but you have no idea how. That means it is very hard to judge who you might be talking to in a chance encounter, so you have to take people more seriously until you find out!

Lastly, a few years in another country makes it hard to ever fit in at your previous 'home' country. The people you left behind seem to have stayed the same, even for decades, as you have moved on, expanded your views, see things differently, refute the bullshit that others take for granted.......

Just my view.....

This really resonates with me, as someone who has also spent much of my life living abroad, although not in Western Europe, mostly in Asia (most recently having spent 6+ years in Thailand). Now that I'm back in the United States and taking care of my aging parents, I feel like such a fish out of water in many respects, and I've been struggling with that "rootless" feeling you mention at the end of your piece.

I wonder, honestly, if the United States, being its own kind of cultural (and even geographic) bubble, is somewhat less forgiving to people who have lived a long time in other places. People are SO sure here that there's a "right" way to live and a "wrong" way that I think they don't know what to do with me, since I haven't done a lot of the things they have (or I did them in the past, but am no longer doing it, like own my own home, etc.), and yet I've done a lot they haven't but that they don't really understand in its full context and just seems "exotic" or "temporary" to them because they can't imagine living that way themselves. I think anyone who hasn't LIVED abroad views others' experiences doing so as a kind of "long vacation" not as a genuinely different way of living (certainly not one that is equally valid).

In reading your piece and reflecting on my own future plans, I'm of two minds. I do like being back here because I've been able to renew family connections and reestablish a more intimate place in their lives... but realistically, the way of being / living in the United States really doesn't "fit" for me anymore. Like you say, I have genuinely changed, and my values and priorities will likely never go back to what they were before I spent so much time living elsewhere (Thailand, India, Australia, and Eastern Europe, mainly). Between that and the political and economic uncertainty here in the States now, I strongly suspect I won't stay here indefinitely. I don't know that I'd go back to Asia, but I could very easily see myself living abroad again, and likely either in Europe or the U.K., where I already have good friends. I recently spent three months in Spain, Portugal, and the South of France, and that felt very comfortable to me (although new, of course). I'm not planning to move again immediately, not with my parents being in their eighties and needing my help, but I think it's pretty likely I won't stay here much beyond where I'm needed here.

Thank you for your thoughtful and balanced piece on this. It's given me more things to chew on while I think about where I'd like to settle next.