One of the questions I presented in my post from two weeks ago, “Are You One of the Few Americans Who Really Could Move to Europe?” was this: “Are you prepared to live far away from your family and friends?” Here, I would like to explore more deeply the topic of having a healthy social network—specifically, of forging and maintaining friendships despite distance. This is incredibly important for those of us who have moved to another country, but it applies equally to anyone who has relocated within their home country, so my hope is that this discussion will be of interest to many people.

Your social network

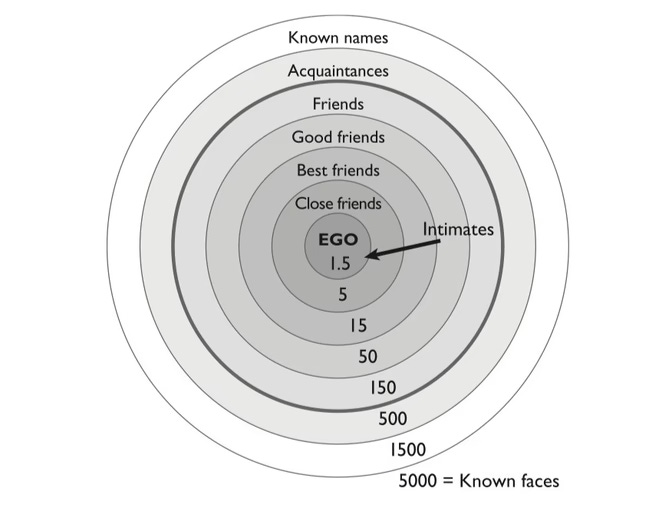

How many people do you know? Robin Dunbar would guess about 150. Dunbar is an evolutionary psychologist at Oxford University and the author of Friends: Understanding the Power of Our Most Important Relationships. Having studied social networks early in human history as well as today, he arrived at the famous “Dunbar’s Number”, which represents the number of individual relationships that we are cognitively able to keep track of: about 150. He argues that this was the average size of human communities when people started living in groups. Nowadays, you may recognize thousands of people, but the number of actual relationships that you keep track of (your parents, your children, your friends, your colleagues, your old friends, the people in your reading circle and your choir, your parole officer, etc.) is probably between 100 and 250. Dunbar also suggests that there is an internal organization of all of these people into concentric circles.

The important point about all these circles is that the people in the inner circles take up more of your time and attention than the ones further out. We simply don’t have the capacity or the time to have fifty best friends. As Dunbar explains in this interview, when we add new people to the inner circles, someone else has to get pushed out to the outer circles. For most of us, this is a fluid and continuous process that goes on throughout our lives, whether we are conscious of it or not.

But what I would like to propose here is that it can be useful to be conscious of it. I am not advocating that we become highly controlling or fixated on our friendship circles, but I am advocating a certain intentionality.

One of the things I like about this picture of concentric circles is that it gives us permission to have different kinds of friends. Not everyone has to be your BFF; it can be nice to know some people who just want to go for walks occasionally, do yoga, or watch football together (whatever sport you think “football” is). In a recent New York Times article, Lisa Miller expounded on the possibilities presented by the “medium friend”—someone it’s perfectly OK not to be in constant touch with but who nevertheless enriches our life in some way.

And of course, in addition to the long-term friendships that we maintain, there is also the undeniably positive effect of having pleasant social interactions with people on a daily basis—those outside the 150 circle. This is one of the things that I love about Portugal (and about Southern Europe in general, as opposed to Northern Europe): people are so friendly and pleasant, even with strangers. Here in Lisbon, I banter with the proprietors of the local restaurants, who might pat me on the arm when I show up for the sixth time.

Here is a typical conversation with the owner of the local grocery store in my old neighborhood (translated from the Portuguese—you’re welcome):

G: Good afternoon, Marlena! Everything good?

M: Hello, Gregory! Fine, thanks. How’s the apartment search going?

G: Pretty well, thanks, but it looks like I won’t be living in this neighborhood anymore—it’s just too expensive. It’s a pity. By the way, have you received the insurance reimbursement yet for the damage the drunk driver did to the store?

M: Nothing, can you believe it? We’re still waiting. So where do you think you’ll live?

G: Probably in Ajuda.

M: Oh, Ajuda’s nice. And it’s on the 742 bus line.

G: Exactly, so I can come back and shop here sometimes.

All this while getting my errands done! Interactions like these absolutely make my day and help me not to feel lonely in my newly adopted country.

But now let’s focus in on our long-term friendships—the inner 50 or so in Dunbar’s diagram. I want to talk about how we keep relationships with those people going when they are far away.

I am now going to tell you something about myself that may make you think I am a total weirdo. That’s OK, I can handle it. But you see, not long ago, I took

’ Sparketype assessment, which is concerned with the kind of worker personality you have, and found that I was an Essentialist-Maker. In other words, I am someone who loves to be creative, and also someone who loves to create order from chaos. This explains, to my satisfaction, my love of spreadsheets.So yes, I have a spreadsheet for my friendships. It’s really very simple: one column for each of my 50 or so closest friends and family members, and one row for each day. Every day, I spend less than one minute ticking boxes to record who I had contact with the previous day—where contact could mean meeting in person, talking on the phone, having a video call, texting, emailing, or whatever. This helps me in two ways: First, it helps me to feel less lonely, because I see how many people actually care about me; and second, it helps me to notice people with whom I’ve gone too long without any contact. I mark these as people to get in touch with soon.

I also do something that I call “Saturday Outreach”. Every week (can you guess which day?), I make a point of reaching out to a person who I haven’t talked to in a long time. It’s usually someone on my list, but it could also be someone I just thought of for the first time in a while, and who I realize I’m still fond of. Reaching out can take the form of an e-mail, a text, a postcard, or whatever; the point is to re-initiate contact with someone I don’t want to lose track of entirely. The other day, after doing this, I got an e-mail that started, “I was really thrilled to hear from you.” And it’s so easy.

Now you may be (and if you write on Substack, you probably are) one of those people who hear the word “spreadsheet” and shriek, raising their hands to their head and jangling their twenty-eight bracelets. But there are plenty of other ways of keeping track of people: You could get a large sheet of high-rag-content paper and a purple fountain pen and write your friends’ names in calligraphy. Or you could get a bunch of post-it notes, write one person’s name on each, and stick them to the wall in the following groupings: “Recently”, “Been a While”, “Ages Ago”, and “Next”. There are lots of ways to do it. The key is intentionality.

I might point out that I do not count social media when I record my interactions, unless they took the form of direct messages. I am very skeptical of the value of social media like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, etc. in terms of maintaining real bonds between individuals. But we can discuss this if you have a different perspective.

The point of all this is to not give up on people. In the twenty-first century, the fact that you are not physically close to each other does not mean you can’t be emotionally close.

Maybe you don’t want to keep track of fifty people—I get that. In that case, here’s what I would suggest: Ask yourself, “Who do I miss?” Allow yourself to be surprised by the answer. Make a list of a few people who you miss—people who would make your sky sunnier if you were in closer contact. And then, one by one, get in touch. It can be as simple as sending a text, saying “You know, I miss you.” Who would not enjoy receiving such a text? Just don’t send it to Obama; he feels bad enough right now.

Far-flung friends

Now I would like to share some tips for managing those long-distance friendships. As someone who has lived for most of his adult life far away from his family and friends, I can attest that this is crucial for keeping up one’s morale.

Different methods of contact seem to work for different pairs of people. I have regular video chats with some friends, and talk on the phone with others. In other cases, contact mostly takes the form of sending funny videos on Instagram and then catching up briefly. The important thing is to figure out what works for both of you, in terms of timing (you may be in different time zones), time available, and enthusiasm.

One suggestion from happiness guru Gretchen Rubin, who gives lots of tips for building friendships in this article, is to schedule regular contact with someone. Having a “phone date” every Friday, or doing a video call every second Sunday, influences people to prioritize the friendship and carve out time from their schedule in a way that sporadic communication doesn’t.

A regular schedule can be especially useful in the case of group video calls, which are a wonderful way to keep in touch with your family or a particular group of friends. If there are three or more people involved, then even when one person can’t make it, the call can still happen.

At the same time, there is a lot to be said for spontaneous, asynchronous communication. I love informal group chats in WhatsApp (or perhaps a less imperialistic alternative), in which people can keep a running conversation going that need not involve everyone; people can jump in and catch up when they have time. An Italian friend of mine has a group chat with about fifteen high school friends that has been going on for decades, even though she hasn’t lived in Italy at all during that time.

Wherever you live, I find it really helps to have a good phone subscription—the kind with good wireless broadband coverage and plenty of data every month, so that you can communicate freely no matter where you are without worrying about charges. (I hardly ever make actual phone calls anymore, since I can use things like FaceTime instead.)

I find that regularity really is the key to keeping friendships going. Yes, the quality of the time spent together is important, but not all time need be quality time. The good thing about having regular (even if infrequent) contact with someone is that it will never feel awkward when one of you suggests getting together, should the opportunity arise. Do you know the feeling you get when you’re planning to visit a city and you realize you have a friend there, but it’s someone you haven’t talked to in a few years? It can be agonizing, trying to decide what to do. The beauty of regular contact, even if it’s only a postcard twice a year, is that it drains the awkwardness out of such situations.

Speaking of postcards, who doesn’t love receiving them? And more generally, who doesn’t love getting a spontaneous message of whatever sort from someone they like? It takes so little to reach out to a friend. I have already suggested writing to the people we miss, but another great opportunity is presented when something reminds us of someone. I recently read a newspaper article about a musician in New York, and that put me in mind of a friend from New York who loves the music scene there, so I sent it to him, just saying “This made me think of you.” Doing this regularly—without much reflection, without making it complicated—is a wonderful way to keep the pilot light burning in the basement of a friendship.

If you are one of those people who tend to agonize over every word when you contact someone (I have a friend who can spend half an hour on a simple e-mail), may I suggest that you try using templates? A template is simply boilerplate text that can be reused with slight modifications. For example, you could have a text file somewhere with templates like this:

Hi ____,

How are you? I saw ____ today, and it made me think of you.

(See below for the link.) I hope you’re doing well. It would be

great to catch up sometime soon.

Take care, and please give my love to ____.

Best,

Brenda

LINK HEREYou may not want to sign it “Brenda”—just a tip. And here’s an even better tip: If you have a hotkey program (I swear by Keyboard Maestro on Mac), you can set it up to paste this or any other template into any document (like an email) at the touch of two keys. A process like this not only reduces option anxiety but also saves time.

But maybe you’re not a high-tech person. Maybe the only way you really like to commune with people is sitting in the sun with a brewski. That’s fine—I can highly recommend the sun here in Portugal, though not the beer. Sometimes we long to spend hours and hours sitting and talking with our friends, face to face. In that case, great—plan a visit. One observation I have made is that spending four days with someone is equivalent to spending the evening with them about ten times. In other words, it’s another way we can spend quality time with the people we like, just parceled out differently.

If you have recently moved, you may notice that the popularity of the place you have moved to is indexed neatly by the number of people who are interested in visiting. When I lived in northern Sweden, virtually nobody wanted to visit me—not even Swedes. Now that I live in sunny Lisbon, interest is far greater. (Thank goodness I don’t live in Venice!) Last year, my ex, Liza, and I came up with a plan for dealing with this—a plan that we never fully put into action due to that one little obstacle of splitting up. But I’ll tell you about it, and maybe you can try it instead.

The idea was, at the start of each year, to decide how many visits we could handle during the year, and set a cap. Then, we would write to all of our friends and family, saying “Who wants to visit this year? First come, first served!” If people expressed interest in visiting, we would start scheduling those trips, up until we felt like we had enough in the calendar. Then we could, in good conscience, say no to anybody else who “offered” to come and see us. This would mean having the year planned out in a way that worked for us, while allowing those who really wanted to visit to do so.

If you, like certain friends of mine who have been living in Portugal longer than I have, find that you get a bit tired of the stream of friends all wanting to visit and see the same things, here’s something you might consider: Plan to do a trip-within-a-trip with some of them, taking them to some part of the country that you want to see. That way, they get to spend time with you and get to see new things—and so do you.

From one perspective, the ultimate way to spend time with friends is to take a big trip together to somewhere none of you live. This could be a new and exciting place that you all have wanted to visit (think South Africa or New Zealand), or it could be somewhere relaxing, like a small town in Puglia, or the coast of Oregon. Planning such a trip can be half the fun, and it guarantees that you will have quite a bit of contact in the months leading up to the event. It also guarantees that you will have lots of memories to talk about in the coming years (assuming that you are still talking afterwards).

I have also heard of groups of people who do the exact same vacation every year, even to the point of booking the same accommodation (this would seem to be ideal for Security people). The advantages of this are that (a) you get to see the same people regularly, (b) these people take it seriously and thus make time for it, and (c) the planning is incredibly easy. These things do make it an attractive prospect.

New friends nearby

If this essay is about having a robust social network after moving, then I would be remiss if I didn’t also address the question of making new friends in your new location. This is probably an essential factor in whether you will ultimately be content with your new home. I know that’s true for me.

So, how to meet people? If you have old friends who have friends in the new place, an introduction from them can be a very handy way to insinuate yourself into the local social environment. And logically, if these people are liked by someone you like, chances are you will like them too. So before you move, ask around to see whether anyone has someone they can put you in touch with. While not everyone will be equally welcoming and helpful, many people probably will, especially if it’s clear that you are planning to stay for a while, and not disappear after a couple of weeks.

But what if you don’t have any such introductions? As I have said elsewhere, I am a proponent of what I call “engineered socializing”. In another essay, I have described the Random Travel Club that I founded and that gave me so much joy for a few years. While that won’t work when you’re new to a place, there are plenty of existing structures you can slot yourself into. Organizations like meetup.com offer dozens of opportunities for meeting people with a common interest, whether that be books, sports, comedy, hiking, yoga, language exchange, or good-old drinking and dancing.

In general, joining any group is always a good bet for meeting new people. You may want to lean into an interest that you’ve had for a long time (or pull one out of the refrigerator), or you may want to challenge yourself to try something new. Let’s say you’re moving to Stockholm, and you like sailing or skiing, or want to learn the fantastically cool sport of långfärdsskridskoåkning—that is, long-distance ice-skating. All you have to do is find a club that is accepting new (novice) members and sign up. Will language be a problem? That depends on two things: where you are, and what you see as a problem. Personally, I love joining a group where I am forced to speak the local language—it’s not only fun, but excellent language practice.

Here in Lisbon, I have started doing something called Biodanza, which is an activity that is hard to describe but easy to enjoy. It is a rigorous method that uses music, movement, and physical contact to help people break down their barriers, deal with their psychological issues, and enjoy the pleasure of human contact, all to awesome music. It is a massive oxytocin boost and one of the most enjoyable things I’ve done—and I have made lots of friends along the way. Plus, it’s in Portuguese, so it’s a great linguistic experience.

But then again, sometimes we just want to get together with one person—and I know many introverts who vastly prefer this scenario. It’s a good idea to figure out what “affordances” your new culture offers for meeting with people. For example, when I lived in Germany, I was completely shocked the first time someone suggested that we meet for breakfast. But then I learned that that was actually “a thing” there. Don’t try this in Spain, though—there, it’s much more normal to meet for drinks (Oh, vermouth!) a couple of hours before dinner (which is at 9 pm or later). Try to figure out what the places and times for socializing are where you live, and make good use of them.

If you are not sure how to befriend somebody (and who is?), here are a couple of things to think about. First of all, people like to be liked. If you show that you like someone, they will probably respond positively. Also, people are far more likely to accept an invitation than to issue one. So if you want something to happen, you should probably just make it happen, rather than waiting for the gods of friendship to suddenly sprinkle connection dust on you. If you want to get closer to someone, try showing an interest in their children, or in their pets—that will always be appreciated. (And of course, pets are a classic device for striking up conversations with strangers, though I don’t think I would use my turtle for that.)

If you are very nervous about socializing, even with one person, you might try inviting someone to attend an event with you. It could be a concert, a film, a reading, a lecture, a dance performance, or whatever. Enjoying such an activity with someone means that there is less pressure to talk, and something to talk about when you do talk. I recently went with Liza to see a performance art piece in which a Japanese man got naked, flagellated himself, and ran around with an electric guitar. Let’s just say there was no shortage of conversation at dinner afterwards.

Another tip for meeting people is to encourage your friends, going to any event, to bring their own friends. I have made lots of new friends this way, by literally having them delivered to my door by someone who can vouch for them. Doing this allows your social network to expand in a very organic manner and brings the other benefits of having a community of friends.

Ultimately, creating friendships takes work. Robin Dunbar claims that “It takes about 200 hours of investment in the space of a few months to move a stranger into being a good friend.” This, he says, is why making a new “good friend” will push a couple of other people out toward the more distant circles.

Our social circles develop and change naturally over time. This process is something we shouldn’t overthink, but it is worth acknowledging that friendship is something we do. I believe that if we approach it with intentionality, maintaining a vital social network is not only eminently doable, but also incredibly satisfying.

Loving the actionable approach, Gregory! Having lived in The Netherlands for a few years, I can confirm that those light-touch interactions you mention (ie., while during errands) are so easy to underestimate but so so valuable. 🙂

I don't keep a spreadsheet, but I do go through texts, lists of calls on my phone, and emails to make contact on a regular basis. I have one friend who calls me when he's driving a long distance, another with whom I chat via Zoom once every couple of months, and the others are text and email.

As a P.S. Yesterday was my "Croatia anniversary", my arrival here for the first time, so I wrote about that day – and the following day, I met my first friend here.I spent 7 weeks in Croatia last spring, so I had a small network here when I made the move in October, but I am trying to be out there more to grow my circle.