How Much Routine Do Humans Need?

On the tension between boredom and anxiety, habit and novelty

Introduction: goals, desires, compulsions, habits

Back in October 2024, I wrote about a few days I once spent on a Baltic island, doing not much more than walking and thinking. That was back in 2016, but I still have my notes from the trip. In my journal, I described a theory I had developed while walking down sandy paths among pine trees, hearing the waves pound the shore nearby.

This theory was about our motivations for engaging in behaviors. I hypothesized that there are four classes of reasons for undertaking an action:

goals

desires

compulsions

habits

These go from most conscious to least conscious. Goals represent things that we actively aspire to do, while desires correspond to a felt urge to do something that we may or may not actively want to act upon. Compulsions represent a stronger, more automatic impulse to act, and often correspond to behaviors we actually would rather not engage in. Finally, habits represent actions we take without even thinking about it much, because the decision to do so has become automatized.

In my journal, I wrote these touching lines about habits:

Habits have their genesis, of course, in one of the other three categories, but I believe that we can persist in habitual behavior even after the original motivation is gone. (I still rub my finger where my wedding ring used to be, three years later.) Habits can be constructive or destructive, so it’s important to think about which habits we want to maintain and which ones we want to change.

At the time, my primary concern was to figure out what was driving my own behaviors. I believe that I concluded that compulsions were behind more of my actions than I was comfortable with, and so that was something I decided to work on.

Today, however, I am thinking more about the automatization that is behind the category of habit. I am interested in the question of routine, and how much of it we want in our lives.

Anxiety versus boredom

If you sleep for a bit more than seven hours per day, you will experience about sixty thousand seconds of wakefulness each day. Say that right now you were to look around the room for five seconds; you would probably see at least five things that caught your attention. These five things might be prompts for possible actions: a coat left on a chair, an unpaid bill, some dirty dishes, a plant that needs watering, a tasty-looking peach. Imagine making sixty thousand decisions per day about what to do. It’s an exhausting thought, isn’t it?

The problem with making decisions is that it is costly. The Dual Process Theory of human cognition, popularized by psychologist Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, proposes that we have two systems for decision-making, one of them relatively automatic and driven by emotions and previous experience, and the other slow, deliberate, and requiring of conscious attention—something of which we have a limited supply.

Quite simply, decision-making is stressful. I don’t know about you, but I find making decisions rather anxiety-provoking. Have you ever had a potentially lovely evening ruined by an argument about where to have dinner? (If so, I have a tip for you below.) In my experience, the days that are most stressful are the ones during which I have to make the most decisions, whether those be about buying a house or managing to run a set of errands. For me, a perfect day is one in which everything just seems to fall into place, possibly because someone else is making the decisions, or possibly because everything has already been planned in advance.

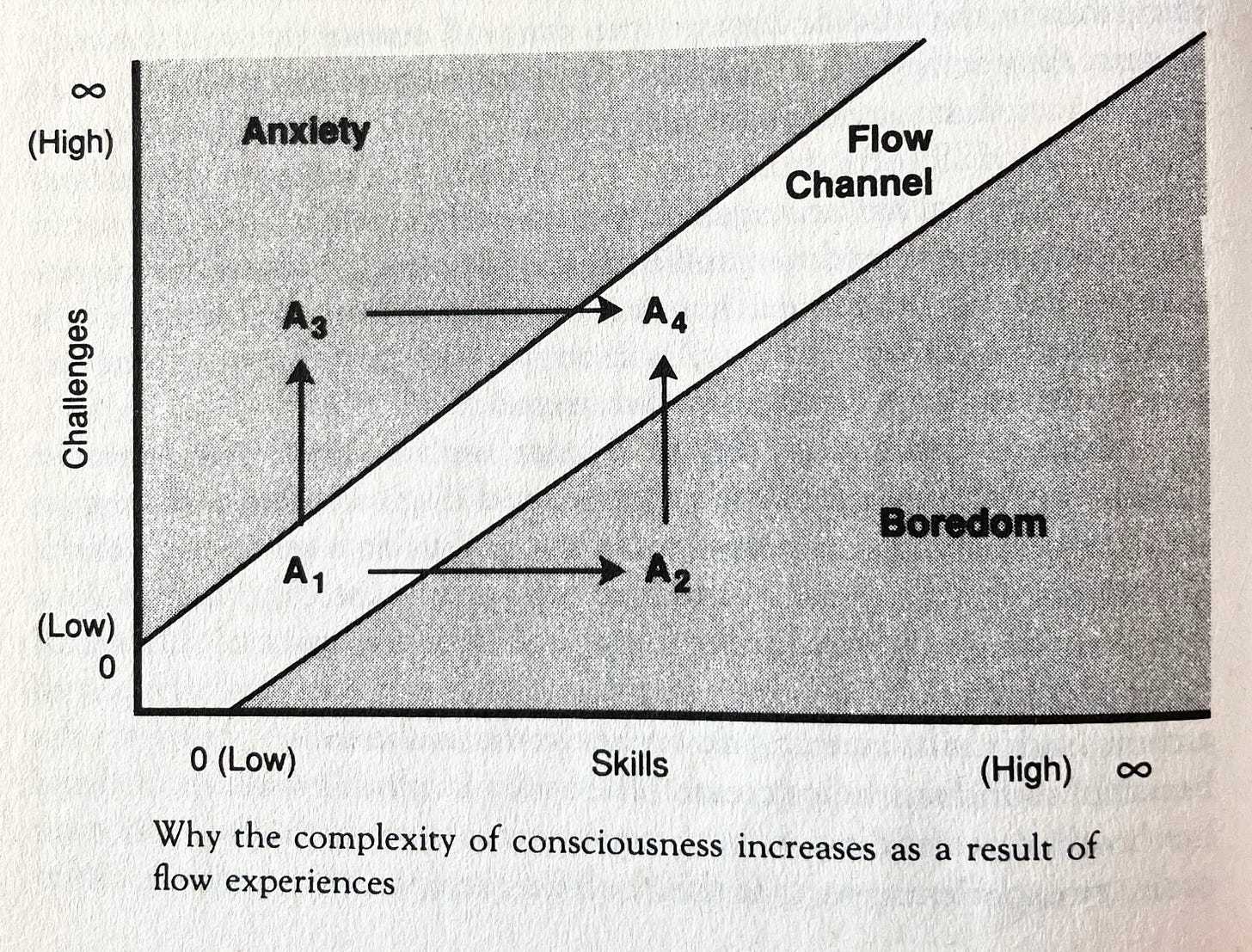

But then there is the other side of the coin: boredom. When do we get bored? When we do things that don’t challenge us sufficiently. One of the most beloved books in my Positive Psychology library is Flow, by the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. One day I may write a whole essay about Csikszentmihalyi’s fascinating concept of flow, but for current purposes, I just want to show you an illustration from the book:

The only thing I want to point out about this is the idea that when we engage in an activity in which the challenges are greater than our skills, we experience anxiety. Conversely, when our skills are greater than the challenges, we experience boredom. This suggests that we can only achieve optimal psychological experiences when we carefully manage the difficulty of our activities.

In short, we experience anxiety when we feel uncertainty or a lack of control. And we experience boredom when we feel a lack of challenge or variation—in a sense, when we have too much control. Now I’d like to talk a bit about what this means for the concept of routine.

Balancing routine and novelty

If we had no routines, every day would be utterly chaotic. Now, I am certain that some of my gentle readers are thinking “But it already is!” To this I say, imagine how much worse it would be if you had to ask someone whether they thought you should brush your teeth this morning, or whether your underpants should go on first. Even on a chaotic day, much of what we do is standardized, and thus falls into the unconscious domain of habit.

Routines support us by ensconcing us in the soft embrace of the automatic, holding at bay the piercing thorns of indecision. A life filled with routines is a placid life. But of course, it can also be a boring life. The central question, as I see it, is how to find a balance between routine and newness.

Two years ago, I spent a chunk of the summer living in a little village in southern Tuscany, in the area known as the Maremma. This village had two restaurants, one bar/café, and one grocery store. If I wanted to go out to eat, it was supremely easy to decide where to go—I just went to whichever place was open. The lack of options made life simple.

By contrast, when I was in Paris recently, I spent hours poring over recommendations for restaurants and wine bars, trying to triangulate among location, cost, and atmosphere. Going out to eat thus felt a bit like defending a thesis. I am tempted to say it was exhausting, but honestly, it was Paris, and it was actually very nice.

So, choice is good, but a lack of choice can also be good.

We all have a need to simplify our lives, to establish good habits and supportive routines. At the same time, we all have a need for novelty. (And when I use that word, I mean it in its basic sense of “newness”, not in the derivative sense of “something of interest only because it is new”.) I believe that people differ a bit in terms of which need is stronger—hence the Security person vs. Discovery person distinction that I presented in the piece “Are You One of the Few Americans Who Really Could Move to Europe?” Nevertheless, I am convinced that we all have both needs.

So if we want to make sure that we stray as little as possible into the gray zones of Csikszentmihalyi’s diagram—avoiding both anxiety and boredom—what goals can we set for organizing our life?

Three goals

Here is my thinking: To find a balance between routine and novelty, we should set the following three goals:

Reduce the number of decisions

Make decision-making easier

Increase variation and newness

Many people smarter than I have made suggestions for methods for reaching these goals, so let me refer to some of them, adding a couple of observations of my own.

Reduce the number of decisions

By now it should be clear both that decision-making can be stressful and that offloading some decisions onto automatic systems can be helpful. In short, we want to form habits—the motivation at the bottom end of my Baltic island scale. But of course, habits can be productive or not, so what we really want is to form good habits.

Many writers have tackled the question of how to form good habits:

in her book Better Than Before; in his book The Power of Habit; James Clear in his book Atomic Habits; Katy Milkman in her book How to Change; and so on.Perhaps I will write another piece one day on my experiences with habit formation, but these authors have already covered this ground quite thoroughly. Here is a small sample of advice they give on how to start turning an activity into a habit:

Make it as convenient as humanly possible to do the activity (e.g. go to the gym on your street).

Combine an activity you don’t really want to do with one you do want to do, so as to form a positive association (e.g. working out and audio books).

Try to avoid “breaking the chain”, but give yourself a pass occasionally so you don’t get discouraged. (See: streak freeze)

Take advantage of moments of new beginnings (new year, new job, new house) to change your habits.

See yourself not as someone who wants to do the activity, but as someone who does the activity (e.g. I am a writer).

The more we can relegate the things that we know we need or want to do to our automatic behavioral system, the more it frees up our conscious mind to think about other things, like the decisions we do need to make.

Make decision-making easier

While it is inevitable that we need to make decisions, I do believe that we can reduce the anxiety generated in the process, by making it more efficient. Let me give just two examples.

The first has to do with scheduling. Over the years, I have spent countless hours obsessing about time management, to-do lists, and systems for organizing my activity. (This was far more pressing when I was an overworked academic.) I have even written several different computer programs designed to help with this. This is yet another topic about which I may write something someday, but for now let me share one thing that I have learned, which is echoed by many of the gurus of time management—interestingly, a field whose value has recently been called into question by

.Very simply, schedule as much as you can in one go. It is much better to spend one hour per week—say, on a Sunday evening or a Monday morning—deciding what needs to be done that week and when to do it, than to spend fifteen minutes sweating every morning (or five minutes multiple times per day), wondering what to do. Remember how I said that for me a perfect day is one in which everything falls into place? One way to make this happen is to wake up and see that you have already scheduled the day’s activities.1

The other example is the method for collaborative decision-making that I promised above. If you would like to streamline the process of making choices with another person, I would suggest that you try my own patented method (ha ha, it’s not really patented) called the Elimination Game. I won’t describe it here, since I have already done so in the first-ever Elsewhere Care Package that I sent out. Normally, these care packages are for paying subscribers only, but this first one is available to everyone.2

I will just say here that the Elimination Game is a fantastic way for two people to make a potentially annoying decision in the fastest, fairest way possible, which allows you to move on to more enjoyable things.

Increase variation and newness

The third goal is the one that is closest to my heart. As a pretty serious Discovery person, I feel a great need for novelty and adventure. This can be something as big as moving to another country or something as small as taking a different route to work. I believe that newness is the key to staying awake and in love with the world.

The way I see it, there are two main approaches to maintaining a sense of aliveness and wonder in one’s daily life. The first is the more obvious one, which is to vary one’s activities.

If you are planning your time in advance as discussed above, why not schedule time for things you definitely won’t happen to do? Here are some examples (with some links for more inspiration):

check the listings of current museum exhibitions and pick one to see

text a friend you haven’t seen for a while and make a date to talk

buy tickets for a concert you’d like to go to

sign up for a course in something new, like pottery or cheese-making

The other approach is what has often been called mindfulness. What I am talking about here is an aliveness to everyday experiences that keeps us feeling connected to the world and grateful for the things in it.

I tried to exemplify this attitude in the recent piece Let Us Now Praise Everyday Things. The basic premise is that if we really look at the things that make up our life, trying not to take them for granted or let them fade into the background, we will see many things that are wonderful and clearly worthy of our attention. This could be something as simple as the warm redolence of a load of clothes fresh from the dryer, the astringent tang of a full-bodied red wine, an errant shaft of sunlight illuminating plums, or the tiny centurions of white spikes on a prickly pear cactus.

It might seem paradoxical that what I am advocating here is both to do things more automatically and to notice things more attentively. But I don’t think there is a contradiction. When I brush my teeth—something that, at this point in my life, I am pretty skilled at—I can still be present and notice the refreshing taste of the toothpaste and the tickling feeling of the brush on my teeth. The reason we want to do things automatically is to avoid anxiety, not to free up the mind to wander. A wandering mind, like any other monkey, can get into all sorts of mischief.

I have written quite a lot about beauty here at Living Elsewhere. This is because I really do believe that trying to be alive to the beauty of our surroundings enriches our lives and helps us to live better. As I argued in The Beauty of Elsewhere, the Beauty of Home, this can be done even when we haven’t gone anywhere special. And we can do it at the same time we are accomplishing other things.

Conclusion: It’s not about society

It is beyond commonplace to complain about our current digital society, with its attention economy and the fractured consciousness that results. But really, the things I’m talking about here are much older than that. It is possible to find writers from a century ago—from two centuries ago, maybe more—who complain about the fast pace of modern life and the stress that it produces.

I believe that as long as there have been human beings, the question of how much routine is ideal has been relevant. We all feel anxiety when we are uncertain or in over our heads; we all feel boredom when we are surrounded by a wasteland of sameness. We differ as individuals, to be sure, but to some extent, we all yearn for the comforting fires of routine and the thrilling hunt for the new.

What have you learned about how to strike a balance between routine and novelty?

I know that people will leave comments here pointing out that life is unpredictable, so let me say that yes, obviously, flexibility is required. You can even build it into your schedule by leaving empty blocks of time, during which you can tackle whatever has come up.

Also, people may be wondering whether this is something that I myself do consistently. I will freely admit that while this is my goal, I don’t manage it much of the time. Is it a bit hypocritical for one to recommend a practice that one hasn’t mastered? I don’t think so. We’re all just humans, and we all find it easier to talk about perfection than to achieve it.

If you think you might like to get more Elsewhere Care Packages, I think you’re right. The simple way to make that happen is just to click the blue button above. Then you will get one in your mailbox every two weeks, and you can go back and read the ones that have already been sent out. In my biased opinion, they are worth it just for the turtle pictures. 😍🐢

This is one of the best pieces I have read on living a happy life. I am about to lose my wife to illness, and I needed a guide to rebuilding. Thank you!

This post reminds me of how my dear mother-in-law always made a plan for a "January project." She would use the dark, long month of January to take on some new activity she had always wanted to learn or do--like reupholstering a sofa, or caning a chair back, or taking a ballroom dance class. She would plan it well beforehand to give herself something to look forward to and then go at it with gusto in January.