“[T]out le malheur des hommes vient d’une seule chose, qui est de ne savoir pas demeurer en repos dans une chambre.”

“All men’s miseries derive from a single thing, which is not being able to sit quietly in a room.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

I love to travel, and I love to be alone. Doing these two things at the same time is one of my favorite experiences. I realize that this puts me in a minority among people. But I don’t think I’m so very different from others; I imagine that most people have simply never considered engaging in solo travel—or have never summoned the courage to try it.

What is unusual is not my appreciation of travel—a majority of people will profess a love of travel—but rather my willingness to be alone. The quote from Blaise Pascal above shows that not wanting to be alone has been an observable tendency in humans for at least 350 years. This particular quote of Pascal’s is much repeated today in discussions of the “attention economy”, because essentially, there are few quiet rooms left in the world. But Pascal’s writing is so rich in sagacious and wry observations that I am going to bring him along on this little journey.1

While we are still packing, let me say what I mean by “solo travel”. I do not mean commuting, and by extension, I do not mean business travel—which is essentially protracted commuting. I am talking here about taking a trip by yourself and for yourself, not necessarily expecting to meet anyone at all. How many people, I wonder, have granted themselves this wonderful experience?

Why do I think solo travel is wonderful? I see four main categories of benefits that it brings, and I would like to walk you through them. Don’t worry, I’ll be right here with you. I have grouped them under the rubrics “freedom”, “openness”, “outward sensibility”, and “inward sensibility”. Let’s set off...

Freedom

“Our nature consists in motion; complete rest is death.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

People often say that they need some time off to “decompress” or “recharge their batteries”—and then to my surprise, the way they attempt to do this is to stay at home, surrounded by their family, doing nothing... but chores. While this may sometimes work, I find that if I really want to recharge my batteries, I put myself in motion: a brisk walk in the sunshine, a trip to the beach, a hike in the mountains, a train ride to a foreign city.

I think that separating yourself from your loved ones from time to time is a kindness both to you and to them (though if you are a mother or wife, much more of a kindness to you—one you deserve). Getting away from the demands of others—or even just the constant interaction—can be restorative and allow the relationship to rest and grow scabs over any current wounds.

Then there is the question of logistics. Sartre said, “Hell is other people”. I would rather say, “Hell is planning a trip with other people.” If you have ever undertaken a complicated journey with more people than your own nuclear family unit, you probably know what I mean. It seems that with each addition of another person to a party, the complexity of the logistics grows exponentially.

I remember meeting some friends in Paris once and going out to dinner. It was two dear old friends of mine, a couple I was very keen to see. However, they had with them her sister, and her husband, and their two children. Going out to dinner with my friends thus became more like a game show in which we had to find a restaurant with enough space, child seats, a child-friendly menu, an American-friendly menu; not too formal, close enough that we could all walk there without getting tired, and not too similar to any place where anyone in the party had eaten recently. You get the idea. This is what travel with a group is like, at its simplest.

By contrast, when you travel alone, you can do whatever you like. You can eat in the restaurant of your choice, or buy a sandwich and eat it on the bank of a river. You can go to a pub and drink several pints before you eat. You can skip dinner and go to bed with a book. It’s all up to you, because you don’t have to please anyone else. This is magical.

“Small minds are concerned with the extraordinary, great minds with the ordinary.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

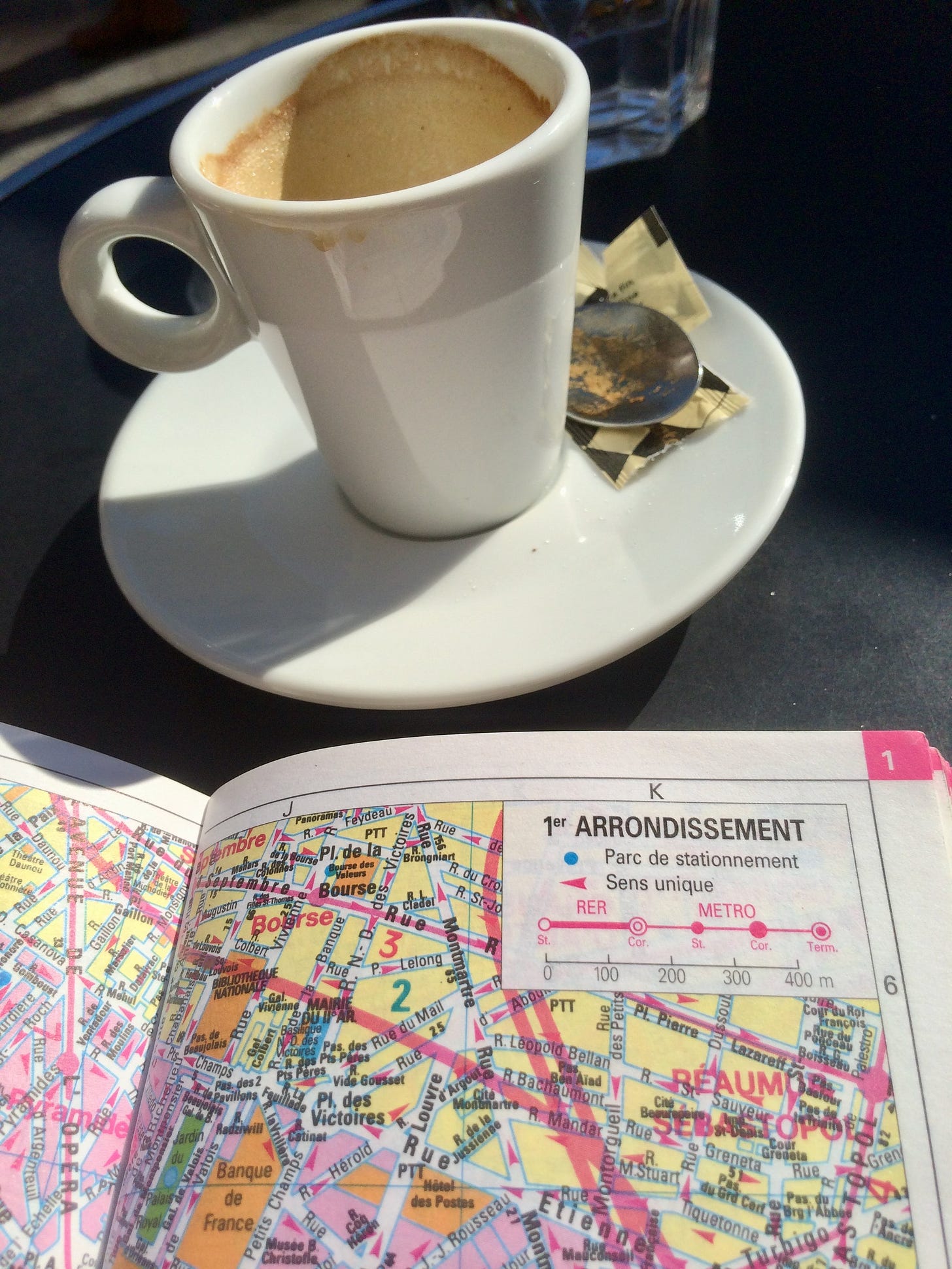

The lack of company also means more time for yourself—not just for doing things, but for thinking. When you have coffee by yourself, you can read a book or write in your journal. Or you can simply stare out the window at the people passing by and muse on the multifariousness of human experience and how random it is that exactly you happen to be in exactly this place at exactly this time.

I will confess that one of my favorite activities when traveling alone is to go to a café or pub, order a drink, and just sit watching people. Sometimes I jot down observations, with a vague intention to use them later. I remember with startling vividness one afternoon in Gent, Belgium—I was actually on a business trip, but these moments can indeed be snatched away from such trips—when I had a couple of hours free, and I found a delightful pub with a beautiful wooden bar, peeling wallpaper, and late-afternoon sunlight pouring through the open doors and windows. I ordered an Orval (the first time I had tried that beer, though you can hardly go wrong with Belgian beers) and sat, watching students and pensioners walk past outside, while I slowly composed a letter to a friend. It was a moment of absolute peace.

“Too much and too little wine. Give him none, he cannot find truth; give him too much, the same.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

Openness

The increased freedom of solo travel also grants an increased openness to experiences. When you are moving about by yourself, you are like an atom that has not yet combined with others into a molecule. There is no telling what opportunities will present themselves—opportunities that would be closed off if you were busy spinning around another person in a tight and oblivious orbit.

Obviously, if you are single, then solo travel presents exciting possibilities for amorous adventures, but I want to focus on all the other ways in which we can meet people. I find that when you are alone, other patrons of cafés or restaurants may strike up a conversation, the owners of establishments are more likely to chat, and you can sometimes start a conversation with a stranger on a train or a plane. These encounters, even if they only last a short while, can provide fascinating windows into places in the world that you would never otherwise have the chance to glimpse.

It also happens that while traveling solo, people make friends. My ex just went to Madeira to see a friend that she met while traveling in Bali. Solo travelers may immediately recognize in each other things that could serve as the foundation of a friendship. But this requires an openness of spirit and a willingness to take chances. Be always ready for someone to ask you, “Are you self?”

“All of our reasoning ends in surrender to feeling.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

Freedom enables openness, and openness enables spontaneity. One of the most exciting aspects of solo travel is that not everything need be planned out. It is possible to surrender to whim and follow your moods, and no one else will be made to suffer. I love to show up in a foreign city with a list of things that I might want to do and then pick activities as I feel moved to try them. Not having a detailed itinerary means that you can also be open to new ideas; scanning the posters on the walls of buildings can sometimes provide entirely unanticipated experiences. Similarly, if you meet new people, they may have suggestions for activities that are far more enjoyable that what you would have come up with on your own. Being open to spontaneity—especially for those of us to whom it may not come entirely naturally—can be both therapeutic and thrilling.

Outward sensibility

“Through space the universe encompasses and swallows me up like an atom; through thought I comprehend the world.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

I have divided the heading of “sensibility”, which I used in the essay “Living Abroad Changed Me as a Person”, into two sub-headings here, because I believe that solo travel brings greater acuity of vision both when looking outward and when looking inward.

As I discussed in the closely related essay, “The Beauty of Elsewhere, the Beauty of Home”, travel opens us to the experience of newness, and with it the experience of beauty. When we are out of our familiar element, all experiences become more intense, and our ability to appreciate what we see feels magnified.

This is especially true when we are not distracted by the presence of other people. It is difficult to embrace the transcendent beauty of the Duomo in Florence while simultaneously discharging parental duties or trying to mollify a lover who feels vaguely slighted. In particular, I love to go to museums alone. If I see a painting that speaks to me, I am free to spend fifteen minutes looking at it; if I enter a room and see that nothing there is of personal interest, I can charge ahead.

A somewhat dubious way of describing this experience is to say that when you travel alone, you are the star of your own movie. This means that you have the freedom to take the director’s role and shape it as you like. But at the same time, since no one else is watching the movie, you are freed of the need to perform. Thus, expectations are lowered at the same time that aesthetics are heightened.

“Clarity of mind means clarity of passion, too; this is why a great and clear mind loves ardently and sees distinctly what it loves.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

Of course, there are many times when we experience something that we want to share with someone. I would submit that that is what photographs are for. Take a picture and decide who you want to tell the story to. This reminds me of another lovely use of photography: I have a friend who makes a point of taking a photograph whenever she feels intensely happy. It can be a photograph of anything at all, as long as it will serve as a reminder of that moment and that feeling.

Inward sensibility

“If we examine our thoughts, we shall find them always occupied with the past and the future.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

Almost as thrilling as the heightened sensitivity to one’s surroundings that comes from travel is the heightened awareness of oneself—but this comes, in my experience, only from solo travel. The problem with which we started this journey—the difficulty of sitting quietly in a room—can be hacked, as I see it, by sitting quietly in a beautiful place. For whatever reason, humans find that an encounter with the sublime—a mountain peak, a stormy sea, a Turneresque sunset—renders the mind quiet and allows profound thoughts to emerge.

I find it easiest to think about my life when I am alone with nature, or in the presence of something else that seems to anchor me with its beauty and majesty. The “thinking walks” that I described in “The Island of the Day Between” are one way in which I try to harness this reaction, marrying reflection to motion. It brings me peace to be able to look over my life from time to time in an inquisitive but reassuring way.

Of course, the ultimate method of putting this into practice is the private retreat, something I have done many times and cannot recommend highly enough. But I will save that topic for another essay, as there is so much to say.

“One must know oneself. If this does not serve to discover truth, it at least serves as a rule of life, and there is nothing better.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

A more practical, though still personal, advantage of solo travel is that it helps us to develop confidence in our own resilience. When you are alone, it is up to you to to solve the problems you come across and make a decision at every fork in the road. The more times this works out well, the more strongly you believe that you can handle whatever life has to throw at you. This is a wonderful way to develop as a person.

Advice for solo travel

This essay is already quite long. I apologize; I have made it longer for I did not have the time to make it shorter.2 But after all my high-sounding rhetoric, I would like to leave you with three simple suggestions for successful solo travel. These are still fairly abstract, but I find them to be helpful guidelines.

First, do not over-plan. I would say that it is ideal to plan the outline (i.e. long-distance travel) in advance, but not the details. It is good to arrive furnished with a list of things that you might do, but embrace the spirit of openness and spontaneity and allow yourself to create the experience as you go.

Second, do not rush. If you must choose between being more ambitious in your itinerary and being less so, always go with less ambitious. Feeling that you need to “get your money’s worth” is anathema to enjoyable travel. Being leisurely is what will soothe you, open your mind, and recharge your batteries.

Third, pack carefully but do not over-pack. I will write more in the future on packing (a topic on which my friends consider me a sort of evil genius), but for now let me just say this: The more carefully you pack, the fewer concerns you will have during your travels, and the more time you will be able to dedicate to things other than emergency shopping. That said, pack as lightly as seems reasonable; if there is something that you can leave behind without missing it, do so. In particular, I find that I always bring too many books; I usually end up buying books on the trip, so I really should just read those. But for some reason, I never learn.

And now, as we return to where we started, I hope to be leaving you with just a bit more enthusiasm for traveling on your own. Just possibly, you need to try it to understand what a magnificent experience it can be.

“Even those who write against fame wish for the fame of having written well, and those who read their works desire the fame of having read them.” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées

I have included the original of the first Pascal quote, because there are so many versions of it in English, and have adjusted the translation. However, for the remaining quotes, I am relying on others’ translation efforts. Also, I believe all of these to be from Pensées, but if you know otherwise, feel free to tell me.

Yes, this is also a reference to Pascal, who is the source of this line, not Mark Twain, as some have claimed.

It's a little more complicated when you travel solo as a woman, though everything you write remains true.

There are, of course, some places in the world where solo traveling as a woman comes with very little risk of any actual danger, but I am here to tell you that the blissful solo slouch through the Uffizi is a whole lot less blissful when you get followed by some dude who stares at you from a not-actually-discreet distance for an hour and a half and then tries to stand in the middle of the exit from a room in order to make damn sure you'll speak to him because he's decided that you're going to do that because he wants you to. And even if -- as in that case -- he stands down without a fuss when you tell him no, firmly, the second or third time, that's a real buzzkill and leaves a girl feeling like it would sure be nice if it didn't seem that some dudes apparently believe any woman temporarily unaccompanied by a man must only be out in public for their sake.

Side note for other women who like to wander around on their own: not reflexively smiling in the habitual American fashion helps, since in many parts of the world the USAian "I'm a nice person, see, I'm smiling!" signals something closer to "well hello there, sailor." So does knowing the proximate local equivalent of "that's rude, shame on you." I have also found it helpful to hang out in any bar/small restaurant with at least a couple of thirtysomething women working there (preferably during a slow time of day), and ask them how they rebuff unwanted attention. There's a substantial cultural element to what works and front-of-house service industry workers, for obvious reasons, ALWAYS know.

That said, I've also had great conversations and enjoyed hanging out with men who I've met while traveling alone. But the unwanted attention and harassment is a thing (and no, I'm not some supermodel, every woman I know has dealt with it to some degree) and it gets super damn old.

I have loved solo travel since my first experience of it at age 22, when I spent six months alone in Europe after graduating from college. Back then, of course, it was quite a different experience from how I travel alone now, some four decades later—I stayed in hostels and worked my way through various destinations in order to be able to continue the trip, then hitchhiked back through Turkey, Bulgaria, and the former Yugoslavia to Western Europe. Now my getaways are generally a week or ten days at most, and I stay in much better (but not luxurious) places, but I do still follow the maxim of not trying to do too much in one trip. I’m an urbanite, so I tend to base myself in one city, perhaps with some day trips.

The main downside of solo travel for me is that it often feels intimidating to think about renting a car alone, having to navigate as well as drive. And there are some rural places I’d like to visit that are mainly accessible by car, especially in parts of Italy and France as well as in Ireland and England.

I empathize with the woman above who mentioned constant unwanted attention and harassment as a downside to solo travel. The good news is that it stops happening when a woman reaches a certain age! All through my 20s and 30s, and into my 40s, this was just the reality that I had to put up with, particularly in southern Europe. I remember once in Sicily not feeling I could even stand still in front of a church, let alone take a seat on a bench, because some man would inevitably come over and start talking to me. These days, I find that many people are still interested in engaging, but often in a quite different way. It’s couples and families at a restaurant or cafe who strike up a conversation with me. I generally welcome those interactions.

One suggestion I have for those who are new to solo travel and are a bit apprehensive—start with what I call “traveling alone together.” I’ve done this many times, usually just with one close friend. We agree to spend some time together in a common destination, but it doesn’t mean we necessarily fly together or have the same itinerary. We may just meet in a certain city for four or five days that overlap. We usually don’t even stay in the same accommodations. But it’s an opportunity to spend as much or as little time together as we want. For me, that usually means a minimum of agreeing to meet for dinner each night. If we are interested in doing some of the same things, we may do them together or we may not. (Like you, I prefer to go to museums solo.) To me it’s the best of both worlds.

My next adventure is going to be five weeks in Parma, Italy, this spring, where I’ll take a couple of weeks as vacation and then work remotely. I love to cook and want to have a kitchen where I can go to a local market and cook the incredible local foods! And I may or may not have some friends join me for a few days here and there; either way, it’s all good. And I’m hoping to take my dog if logistics don’t get too complicated…