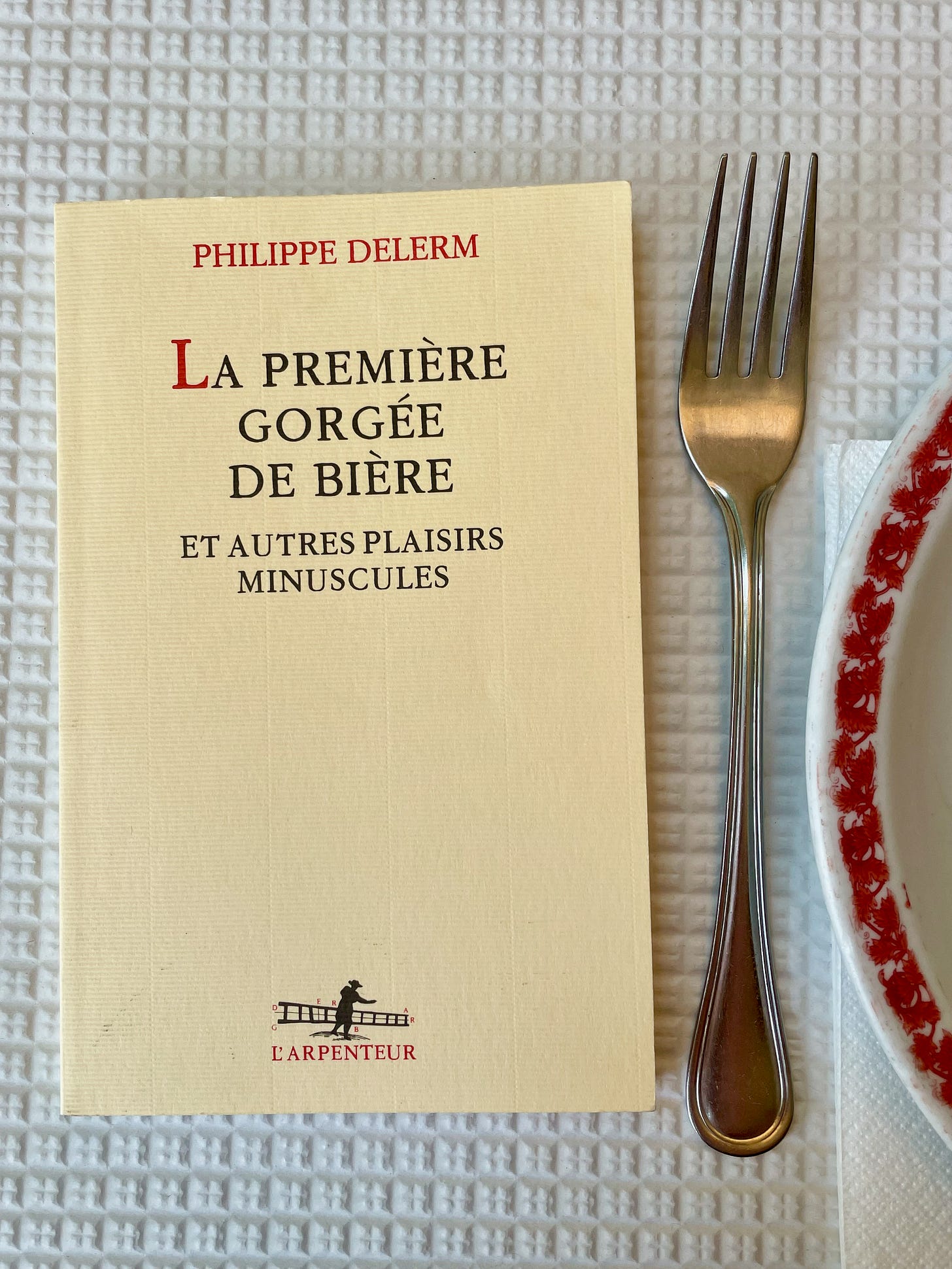

Recently, I have been reading the delightful essays of Philippe Delerm. His pieces are short vignettes that celebrate the minutiae of life in an astute and tender way. This brings me great pleasure, and it reminds me of how much I appreciate the American tradition of essays celebrating the quotidian, from Henry David Thoreau to James Thurber to

. In that spirit, I offer the following series of vignettes of my own. I hope that they will cause you to stop and smile, and possibly even sharpen your appreciation of the immediate world.A Hot Shower

Here is my solemn belief: Every day, we should get down on our knees, raise our eyes to the heavens, and thank our ingenious forebears for giving us the magnificent gift of hot running water.

It is mid-morning. I have done some work, and even some exercise. My breakfast is complete, the dishes have been dispatched to the sink, and I am now ready for that event which marks my transition from a growling bear in a den to a stag ready to bound through the forests: a hot shower.

I strip off my clothes and leave them on the bed. I pad into the bathroom, accepting the annoying whine of the fan in the knowledge that it will save me from a suffocating fog. I step into the tub and turn on the water.

For the next minute, I play hide-and-seek with the stream of water. Over and over, I stick in some part of my body, to see if it is still cold enough to cause a shiver or already hot enough to elicit a yelp. Then, as the temperature approximates the point of perfection, I become Goldilocks. Standing under the hot spray, jiggling the lever with the finest of movements, I twitch the temperature until it reaches the perfect equilibrium, sending me into ecstasy. It is warm enough to be comforting, without being overpowering, like a womb composed of thousands of droplets. I feel warmed, I feel protected, I feel loved—a happy childhood every morning.

I wash my hair, I soap my body. I enjoy the feeling of the water hitting my head, sliding to my shoulders, taking a ski jump off of my back, and landing on my buttocks with a slight tickle. Everything is pleasure. The only conflict lies in the question of whether to lower the temperature to rinse my face or bear the supernova blast for a few moments.

A shower is a guilty pleasure: I know I am using more water than is strictly necessary. I am also burning the earth’s fuels to heat my body. But this is a guilt I am willing to accept. There is no drought at the moment, and I am more than happy to pay for this privilege. The amount of pleasure the event brings me is worth any price.

The water off, I reach for the towel, vigorously rub my head and my body, swath myself, and step out onto the bathmat. I walk out of the warm fug of the bathroom into the bracing cool of the hallway and delight in the contrast. My body is clean; I am alive. I am a gleaming stag, ready to leap through the sun-dappled forests. How could the day not be a success?

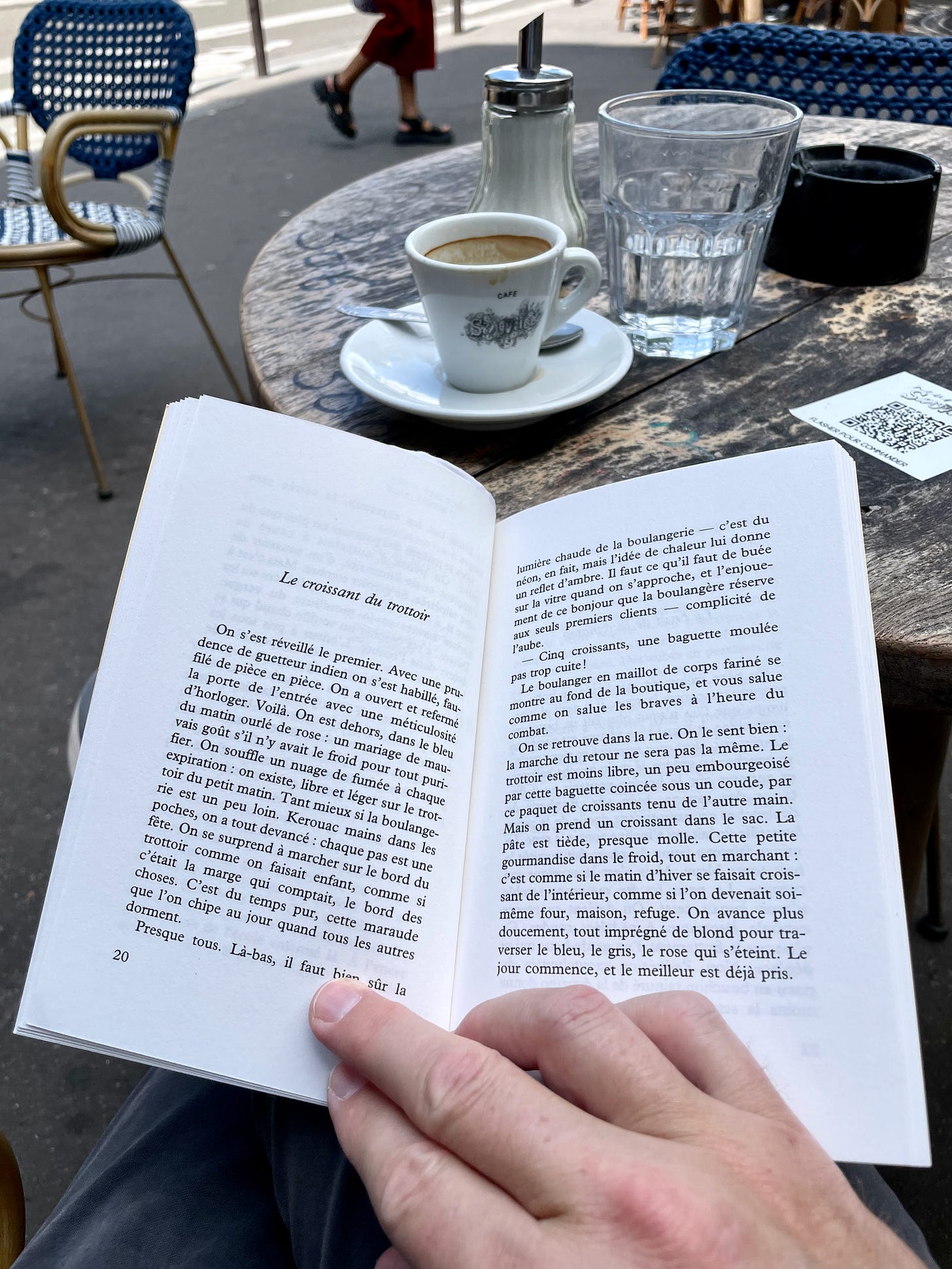

The Espresso

I smile at the woman behind the counter, who has an amused look on her face—what chaos will this foreigner bring to my establishment?, it seems to say. Her face brightens and turns even more amused when I order a coffee and a savory pastry in a Portuguese that is both fluent and idiomatic. She works the espresso machine with a whack-whack-shhhhh sound that kindles my anticipation.

She hands me these treats, and I sit down at a small marble-topped table. Now comes the ritual of the sugar: I take the packet between two fingers and shake it, shicky-shicky-shick. Then I tear the top end, taking care to leave the two parts attached, as I have no desire to chase any fluttering bits downwind.

I look at the dark, creamy liquid with its roiling crema, and silently apologize to it for the invasion it is about to suffer. Before pouring the sugar into the steaming cup, I pick up the diminutive spoon and put it in my mouth to warm it—nothing shall endanger the process. The sugar slides out of the packet with a shhhhhhifff sound and sinks into the brown liquid. I take the spoon from my mouth and begin to stir with a dull, repetitive tinkling.

The Portuguese are dedicated stirrers. Sometimes they can stir a coffee for minutes on end. But I, a simple newcomer, am less committed to ritual and more eager for the rush of caffeine. I stir some twenty times, retire the spoon, and grasp the cup by its tiny ear. This moment is the pinnacle of the day. Raising the cup to my lips, I inhale the rich, nutty steam and take a sip of the bittersweet suspension.

The taste is not just a taste—it is a rush of emotions. It is as though I were being injected with the essence of human history. The steaming liquid carries all of the sweetness of civilization’s successes, and all of the bitterness of its failures. I travel back in time to a mountainside in Ethiopia where a goatherd finds his flock frolicking. I travel to a coffeehouse in London where Issac Newton and Robert Hooke discuss the nature of gravity. And I travel back through my own infinitesimal history to my first year in Europe, at the age of nineteen, when the whole world stood wide and beckoning, and I had not yet learned any notion of failure.

Strolling Through the Station

The perfect time to be in a train station is when you are not going anywhere. There is something lazily luxurious about wandering through the doors and looking around at all of the puffing travelers. They swerve left and right, while you travel in slow motion. The stress and confusion that they exude cannot touch you in your bubble of lassitude.

Your eyes rise to the soaring vault of the roof—all of that steel and the countless rivets. You see the windows that admit less light now than they did a century ago. You spend some minutes admiring the paintings high on the walls, painstakingly done and overlooked by thousands every day. You gaze at the giant departures board with its glowing letters, names of cities prompting wild fantasies of escape and adventure. Train numbers, departure times, platform designations—the minutiae of the moment, never to be repeated exactly. All of this you can sweetly ignore.

Perhaps you pause to examine a map of the station, thinking that a better knowledge of the platforms will serve you well in the future, on a day when you have somewhere to go. On an impulse, you walk to a café inside the station and order a coffee, or even a beer—payment upon delivery, due to the swirling uncertainty of the milieu—in order to sit and watch the travelers go by in their subtle but infinite variety. There are businesspeople tightly clutching their phones; parents tightly clutching their children; tourists with maps and jaws held slack; young couples embarking on their first trip together; a very old woman, possibly going to visit her son for the last time.

You watch all of this activity and marvel at the nature of life. Civilization has given us so much, but it is, after all, merely possibilities—it is up to us to color in the spaces and make a real life. The trains are nothing but vectors, ready to take us here or there. What we will do here, what we will do there—that is for us to decide. Watching life unfold in a thousand directions, you feel a gratitude to the forces that propel us forward, and you say a silent prayer that you will never forget that your job is to choose your destination well.

Asparagus

The bundle is defined by two robust rubber bands; when they are blue, I think of Miles Davis—green in blue, not blue in green. Inherently directional, the bundle points one way and not the other. I remove the elastic guardians and allow the vaguely fascist symbol to fall to pieces. Now I have a platoon of soldiers, ready for battle.

Washed, they lie at attention on the cutting board. Feeling the queasy misgivings of the executioner, I heft a Japanese chopping knife and grasp the stalks, one by one. The method never fails: a blow near the base, which doesn’t cut quite through. Another blow, further up—almost. A third blow, which cuts clean through the stalk. Now what remains will be tender and delicious. Having performed this inverted circumcision on each stalk, I dry them with a towel and leave them to recover.

The pan gets very hot over the jets of gas, and the olive oil starts to thin and spread. Into the pan go the asparagi, where the slight water remaining on them causes a brief hiss. I use three fingers to take generous pinches of course-grained sea salt, rubbing the fingers together over the pan to release all of the grains. Now it is merely a question of wrist and eye.

With a glass of cold, straw-lemon wine in one hand and a plastic spatula in the other, I stand over the pan, humming to the song emerging from the speaker or making conversation with a guest. I roll the little green rods around, as they slowly transition from masculine to feminine: becoming ready, they soften. The green becomes intense, and they develop a sweaty sheen. A flick of the wrist tells me that they are almost there—at the point of being pliant but still with a crunch. The nutty, woody aroma rises from the pan and sets my stomach to whining like a dog.

And then: “Done.” Like a field marshall, I make the decisive call and sound the retreat from the heat of battle. Platter in one hand, I scoop up the fallen soldiers three at a time and arrange them for their last rites. They have served bravely, making the ultimate sacrifice that we shall continue to live.

The Crown Jewels

There is nothing more gorgeously electrifying than the arrival of your lover. The bell rings one rainy evening—or better, one hot and still afternoon. You open the door, and she is there, with an amused smile that portends great things. You kiss, first perfunctorily, then voluptuously. Perhaps you offer her a coffee, or a glass of wine. She accepts, and you open a cold bottle of crisp white wine with a festive “pock”, and pour two glasses.

But your focus is on the magnificent ritual of the jewelry. After kicking off her shoes, but before undressing, she walks barefoot to the table—possibly the dining room table, perhaps the nightstand—and proceeds to relinquish her ornaments.

First one ring, silver and heavy, hits the wood of the table—ca-click. Then another, smaller—click. And a third—click. The watch clasp opens with a tiny sigh and the timepiece comes down heavily—clock. And then a bracelet—shlick. She hesitates, fingering the necklace, and decides it can stay on. Finally, she removes her earrings, with that look of distracted concentration that drives you wild with desire, and they join the collection—tink, tink.

As you hear the feline sound of zippers behind you, you stare at the ensemble on the table, looking as rare and as precious as an exhibition of the crown jewels, and you feel the thrill of being that supposedly impossible thing: a rich man about to enter the kingdom of heaven.

If you enjoyed this, you might also enjoy the following pieces:

You write about the everyday in a way that makes them little jewels sparkling before me. Thank you 😸

so many small but profound insights here, and turns of phrase so pleasing they feel like candy. i love the slowing down to the point where everything becomes sensual. even asparagi! (i had to look it up to see if that is actually a word or you were just being silly. turns out it is! new info i will integrate into my vocab. its use here is quite fun.) hot showers - as good or better than therapy for sure.