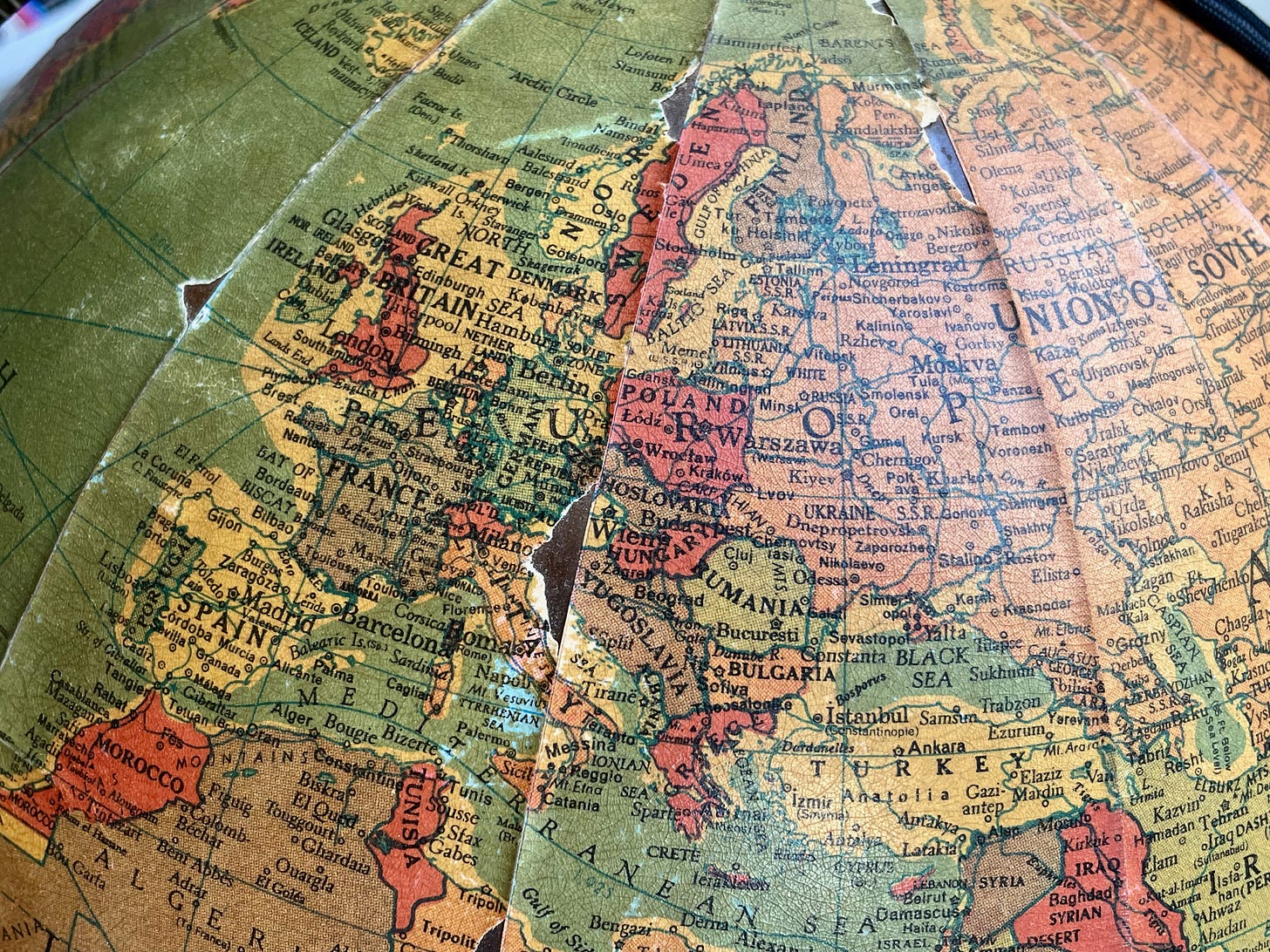

When I was younger, I was restless. I had a fear, similar to that which would, years later, come to be called FOMO—but really it was FONBITRP: the fear of not being in the right place. I had grown up in places that felt simply “wrong” to me—not just uncool, but somehow out of line with who I inherently was—and so I went in search of a place that was “right”. An important aspect of this was a desire to be in the center of things, so I sought out large cities: Boston, Lisbon, Madrid, Paris, Berlin, Stockholm. It took me years to come to an understanding of this desire, which bordered on compulsion, and even longer to find an alternative.

This is an essay about various interlocking tensions: moving away versus moving toward, seeking versus committing, adventure versus home. Together, these produce enough tensile strength to form a bridge from one era of life to another. I want to tell you about my journey over this bridge, and maybe you will tell me about yours.

I remember an experience from my first period of living in Lisbon, in my early twenties. I was a teacher in an institute, working with several other young people. One of these was a clean-cut young American who, promptly after arriving, fell in love with a Portuguese girl (I can’t bring myself to call her a woman—she wasn’t even twenty). They started dating, and within a year, were making plans to marry. I couldn’t believe it: My colleague was planning to settle down and spend the rest of his life in Portugal! This provoked in me a horror that I find intriguing today.

I think my mindset was that young adulthood is like a discotheque: You stay until it closes. You don’t come for just five songs and one Malibu-and-Ginger Ale (please don’t ask) and then go home. There was a greediness in me, a desire to see and do everything, a hunger to consume the world. I think I felt that my colleague, in choosing to marry and settle down at the age of twenty-two, was forfeiting the best part of his life.

But there was also that fear: I did love Lisbon, but was it the Center? I felt I needed to be right in the middle of things—where it was all happening. While in the Portuguese context, Lisbon might be seen as this center, in the European context, it surely was not. So after two years, I left.

I moved to Berlin, which felt a bit more like the Center. The East and the West had recently reunified, and chaos abounded. It was messy and beautiful, and in many ways, I loved it. But there was something about German culture that just didn’t feel right to me. I couldn’t see myself choosing to live there for the rest of my life, or even a long time, so after a couple more years, I continued moving.

That, I think, is plenty to paint a picture of my peculiar peripatetic life. What I see now is that it was a process of both moving toward and moving away—I was pursuing, but I was also fleeing. I suspect that this pattern is common to many people, and since it is not the healthiest of patterns, I would like to explore it a bit.

What was I moving away from? For one thing, there was my FONBITRP, my fear of not being in the right place. I actually see this as a manifestation of moving away more than of moving toward, because all I ever really knew was that where I was didn’t seem right. But I never did find a place that truly represented the Center. I was also probably fleeing childhood issues that I had not fully worked through; when you move somewhere else, it is easy to convince yourself that you have left your ghosts behind and they won’t be able to find you.

When I left America, I was also moving away from the society in which I had grown up, but which had always felt eerily foreign to me. I always harbored suspicions like those of an adopted child who has not been told the truth. Perhaps I should give an example: I had been raised by a single mother, and I could not fathom why people would disrespect women—and yet everyone around me did. Also, I was forced to watch the Dukes of Hazard.

So what was I moving toward? Certainly, I was looking for adventure and discovery—and beauty. As I wrote recently in “Finding Beauty in Ugliness”, the search for beauty has always been a motivator for me. I was also hoping that I could find a cultural context that would be a better fit for who I felt myself to be. With hindsight, I realize that I yearned desperately for belonging, but didn’t know quite how or where to find it. I simply had a vague sense that if I kept looking, I would find a place that would say “home” to me.

The thing that might well have destroyed me was a certain perfectionism overlayed on top of all of my yearning. I was critical, and found fault with all of the places where I lived. In Lisbon, I couldn’t find a way into the society; the Portuguese seemed no more eager to welcome a foreigner into their fold than they were a dolphin. And I wasn’t willing to do what my colleague had done: to marry into the society and thus enter by force. In Berlin, I found friends, but no community apart from jaded, hard-partying youths, of whom I tired quickly.

I believed that if I simply kept moving, kept searching, I would find the perfect place for me. Settling down in the “wrong” place seemed like a kind of defeat, even a kind of death. This attitude is dangerous, because we cannot try living in all places, and none will ever turn out to be perfect, so I ran the risk of engaging in an endless search.

Looking back over my wanderings, I see that there are several questions that encapsulate the quandary I was in:

Are there things we can escape, and others that we can’t?

Is there really a place that is inherently right for a given person?

Is home something we find, or something we create… or both?

What does it mean to belong? Is it a question of finding or of creating a community?

In a sense, all of these boil down to the question of how much responsibility we bear for shaping our own life. I used to believe that the right life was out there, waiting for me. Now, what I believe is not so simple.

This brings us back to the so-called “fixing” debate: Will moving to another country solve your problems? I would like to think that the discussion is swirling around and around and toward a central point, like water going down a drain. That point represents the acceptance of two facts:

Our context does influence us, and it provides us—or fails to provide us—with the resources we require.

But ultimately, our life is lived inside us; we are the architects of our own emotional edifice.

As I argued in “Do You Need to Fix Yourself Elsewhere?”, we stand to gain by choosing the right place to live—one where the conditions of life are benevolent and the community shares our values—but that is no guarantee of happiness. To have a good life, we need to work, and not just for a living—we also need to work on ourselves.

The hard-won perspective that I have today is the fruit of many years of struggle. The core of what I have learned is to be centered in myself. Not self-centered in the sense of selfish, but centered in the sense of not feeling a need to be anywhere other than where I am, or to be anyone other than who I am.

I only had a chance of attaining this perspective after learning the lesson, gradually and with many setbacks, that perfection is unattainable. Both people and places must be accepted for what they are, and not asked to be different. And that includes myself—I learned that I had to forgive myself, too, for being imperfect, and accept the disappointing and tangled jumble of traits that make up me. Doing that—accepting who I am—meant that I no longer had to keep moving, looking for a place where I would be forced to be different, to be better.

It would be unfair of me not to point out that this is a lesson that—for those who learn it—usually comes with age. Some studies (though not all) and my own experience suggest that most people reach the point of self-acceptance, and of accepting what life is and what it is not, only after the age of 45 or so.1 For some, it comes many years later; for others, not at all. An important component of this change is relinquishing the youthful view (which I had in spades) that life is infinite, that the whole world is there for the taking, that everything is possible. Instead, we learn to accept that there are only so many days in a human life, and thus there are many things we will never do. Not only is this conclusion inescapable, but it also gives us a great gift: the ability to refocus our vision on what is nearby and learn to appreciate what we already have.2

This refocusing is the trip across the bridge from adventure to home. Like the protagonist of Paulo Coelho’s ridiculously popular novel, The Alchemist, we can go off in search of a treasure, traverse the entire world, and then discover that the treasure was, in fact, buried in our own backyard all along. Our adventures form the backdrop against which we see and appreciate what we have when we settle down.

Or not. There are powerful forces conspiring to hinder us from ever feeling content with what we have—indeed, the entire consumer society is designed to prevent this. There are innumerable people (especially in the United States) who actually have everything they really need, but feel unsatisfied, because their eyes are focused on that which they do not (yet) have. The more these people earn, the more they spend. The more they have, the more they want. This is excellent for the economy and dreadful for the individual.3

Am I immune to this pattern of endless longing? Not immune, no, but I feel that I have now learned to limit it somewhat. Let’s talk for a moment about the concept of home. I tried for many years to feel at home in Sweden, a country that welcomed me and provided me with a luxuriously permanent position at a prestigious university. But I failed. For all of the work that I did on myself, I was unable to feel truly centered with the resources I had at my disposal there. This led me to renounce everything and embark on an adventure of exploration with my then-girlfriend Liza, my turtle, my begonia, and my sourdough starter, which lasted over a year.4

The difference between this odyssey and the peregrination of my youth was that this time, our explicit goal was to find a home—not the perfect place, but a place that was good enough. Crucially, we had to agree on what would become our home (I mean Liza and I had to agree; the turtle, the begonia, and the sourdough starter really had no vote), so compromise and accepting imperfections were the order of the day.

In the end, after many months of travel, we chose Lisbon, the city that I had rejected three decades before. Do I now see Lisbon as more perfect than I did then? No. Now, I accept it for what it is, with all its shortcomings, flaws, and peculiarities. And I think I can say the same of myself. Here, I feel like a pigeon. Lisbon gives me just enough of the raw materials that I need—sun, beauty, stability, sociability—to construct a nest for myself.

But now I understand that I bear the ultimate responsibility for my own emotional well-being, for being the centered person who knows how to enjoy his own life. It is not easy, but at least I have the marvelous gift of agency, of knowing that what I want is within my reach, if I hold out my hand and grasp it.

So what is home? There are many pieces here on Substack that address that question,5 but I will share my own definition: For me, home is the confluence of a place and a state of mind. It is a place where I can feel centered and at peace, a place that stills the desire for change.

And here is the best part: The more I work on myself, the more I develop a facility for achieving peace of mind. This means that there are more places that can potentially feel like home. My aspiration is to one day be like my turtle and carry my home on my back—not the physical part, but the emotional one. This would obliterate the distinction between home and adventure, meaning that I could live my life as fully as I wished, while never feeling the need to be elsewhere. No more FONBITRP for me—the ultimate goal is to become the Center.

See, for example, “The U-shape of Happiness Across the Life Course: Expanding the Discussion”.

For a discussion of appreciating things we already have, see my essay “Investing and Returning”.

Please note that I am not claiming that this applies to everyone in the US; I am well aware of the level of poverty there. But I am also well aware of the level of wealth concentrated in a sizable minority of the population.

For the story of me quitting my permanent job, see “How Dare You Change Your Life”, and for the story of how that came about, see “The Beginning of a Great Adventure”. Sadly, I still have not written the story of my 30,000-kilometer trip around Europe with Liza. Maybe one day I will.

How fitting that you're maturing and learning acceptance brought you back to the place you first rejected. (Not counting the U.S. of course.) You couldn't have planned it better all of those years ago.

I also always felt like an outsider in the U.S. but I always wondered if it was because I felt like an outsider in my own family. But the first time I set foot on foreign soil, I knew it was more than that.

The thing that surprises me now is how at home I feel wherever we are living in the world. After two or three days, it feels pretty damned normal. Perhaps I carry a bubble of acceptance with me that no place is perfect? And to a lesser extent myself?

Dunno, but I'll keep traveling and thinking about it!

So many thought-provoking questions in this one, and I'm still trying to figure out where home is/was/will be - past/present/future all wrapped into one. I'm 48 and I don't think I've hit the self-acceptance stage yet either, other than to accept that I have no idea how I ended up in such a damn pickle!

These are the three questions that I could ponder for ages and never come up with an answer:

Are there things we can escape, and others that we can’t?

Is there really a place that is inherently right for a given person?

Is home something we find, or something we create… or both?

What's with the Malibu and Ginger Ale? 😂