Do You Need to Fix Yourself Elsewhere?

Or, what kind of transplanting do you really require?

I have a friend who has a large, Y-shaped scar on her abdomen. When she was in her twenties, her liver suddenly started to fail. She was about to die when a team of doctors successfully removed her liver and gave her a new one from a donor. That transplant saved her life. Today she is healthy and has a family.

When we speak of organ transplants, we are actually using a metaphor. In the first instance, transplanting means uprooting a growing plant and planting it elsewhere. Generally, we do this when we want to move it, or when we think that the plant would benefit from a new environment. Conversely, in the case of an organ transplant, it is actually the new environment that benefits from the transfer.

And there is, of course, a second metaphorical use of the word “transplant”, which we employ when we move ourselves or others to a new location. Ideally, this is done for the benefit of the transplantee (though sadly, this is not always the case). This essay is about transplanting yourself: when it is—and when it isn’t—the best way to increase your well-being.

The “fixing” debate

Over the past several months, a sort of debate has been slowly swirling around the tides of Substack, among those (like me) who write about living in other places. Recently,

wrote a beautiful and insightful piece entitled “A Day Spent Here Is a Day Not There”, in which he explores and moderates the debate to some degree. He divides those involved into two camps: the Fixies and the Wherevers. Please see his piece for the full description, but essentially, the Fixies believe that changing your location can be the key to changing your life, while the Wherevers believe that you take yourself and your problems with you wherever you go.1In that essay, Dan admits that he was unable to put yours truly into one of the camps, as I seem to exhibit some aspects of both groups. That is exactly right, and soon you will understand why.

Given that we seem to be witnessing the precipitous destruction of the institutions that make America a functional and upstanding nation, it is not surprising that many citizens are asking themselves whether the US is still a place they can call home. I want to offer these people my sympathy and say that much of the rest of the world shares their incredulity. Fortunately, there are many of us who left the United States (and other countries) years ago, and have many helpful stories to tell about living elsewhere.

If you have seen my piece entitled “Are You One of the Few Americans Who Really Could Move to Europe?”, you will understand that my primary message to anyone considering leaving is this: Please don’t think it will be easy. (I also tried to make this point in the interview that I did on Elizabeth’s podcast.) But this does not mean that moving abroad is a bad idea. I tried to explain this in “Living Abroad Changed Me as a Person”. Here, what I want to do is explore the question of how and when moving abroad actually can fix you—that is, improve your life.

What is your life?

I want to go to a slightly philosophical place for a moment, and I hope you will come with me. When we talk about changing our life, what do we really mean? Here is a proposal for how to think about it: Your life is nothing more than a string of experiences. Each experience is like a coin with two sides: the physical side and the mental side. The physical side is what “happens to you” on the outside. Let’s say you go to the dentist, who drills a hole in your tooth and fills it with some sort of amalgam. (As an aside, isn’t it strange that most of us have no idea what kinds of materials we have in our own mouth? But let me not freak you out too much.) The drilling and the filling are the physical side of the experience.

Then there is the mental side, which is somewhat independent. This has to do with your thoughts and your emotions, which we can posit are inseparable, as emotions are caused by thoughts, and thoughts can be influenced by emotions. The question is this: How do you react to the experience at the dentist? I have noticed that people vary widely in how they react to dental work. Some start to panic long before the visit itself, while others remain calm and don’t get too bothered by it. (I am actually in the second group, in case you were wondering whether these people really do exist.)

An experience can stay with us both physically and mentally. Your new filling will hopefully continue to do its job through hundreds of sandwiches and caramels. And depending on what happens in your brain, you may carry away from the experience a trauma, or only a vague memory of something you read in the waiting room about Richard Gere.

The Maslovian hierarchy

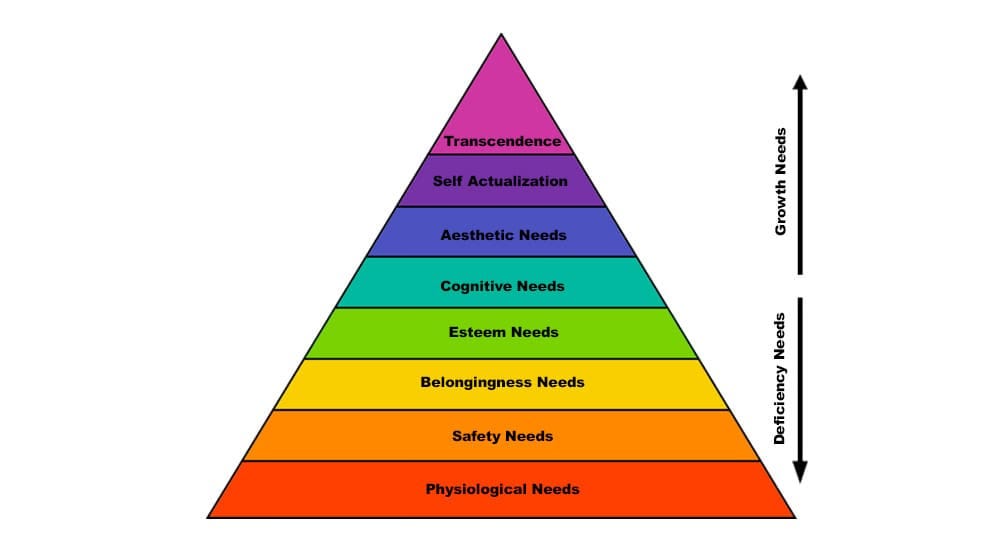

You have likely heard about psychologist Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs. Many of us are familiar with the pyramid representing the five levels of human needs, from the most basic (food and water) to the most sophisticated (self-actualization). But in fact, later in life Maslow decided to add further levels to the model, resulting in a pyramid with more strata, as illustrated here.

Note that these needs can be grouped further into deficiency needs—including the need for food and shelter; for safety and security; for family and friendship; and for self-confidence and respect—and growth needs—including the need for learning and understanding; for beauty and creativity; for the realization of our potential; and for spiritual experiences and service to others.

Is this relevant to moving abroad? In my view, it is. Let me explain how.2

We all need fixing

I believe that we all need change. I am sure that there are a few people who are 100% mentally healthy and 100% emotionally stable, but I suspect that they don’t spend a lot of time reading Substacks about living abroad. So for the rest of us, the question is how we can best fix ourselves—meaning, how we can best move up the Maslovian pyramid until we are fulfilled at every level.

The big question, I believe, is whether that change needs to be outside us or inside us. If your life isn’t what you would like it to be—meaning that the string of experiences you are having is leaving you unsatisfied—the question I would ask is whether the problem is with the physical side or the mental side of each coin. In other words: Do you need to change your surroundings, or do you need to change yourself?

Here is why I don’t see myself as either a Fixie or a Whatever: I think that different people have different needs, and the worst mistake you can make is to fail to understand what you need.

Changing your location is not certain to fix you. Take me to any city anywhere on the planet, and I’ll bet I could find a person there who is almost perfectly content with their life, and another who is perfectly miserable, despite living under the same conditions. While our surroundings can have a major influence on us, they are not determinative. You could move to a gorgeous house in Sorrento overlooking the Gulf of Naples and spend all your time being angry at your mother-in-law.

At the same time, some people may live under conditions that are so abhorrent that it is not reasonable to expect them to achieve real happiness, let alone self-actualization. Here I am thinking of places like Gaza, like Ukraine, like South Sudan—not like Miami or Cleveland.

But there is quite a lot of ground in the middle. Let’s look at two different scenarios.

Maybe you need to be transplanted

Your immediate environment does have a major impact on your lifestyle and your quality of life. It conditions your level of security, who you interact with, what you see every day, and what resources for personal growth you have at your disposal.

Here is what I suspect: Moving to another country makes the most sense when the needs you are struggling to meet are toward the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy—the deficiency needs. All refugees know this. If you are a trans person facing threats to your physical safety, or a woman facing challenges to your bodily autonomy, then moving to a safer environment could make sense. Similarly, people who are facing financial ruin because of the cost of healthcare where they live have a good reason to move to a place where healthcare is considered a right (i.e., a normal country). That said, greed is not a motivation that I can endorse; many people want to leave their country simply because they wish to avoid paying taxes. I see this as unfortunate, short-sighted, and unlikely to lead to happiness.3

Or maybe you live in a country (like I did) where you felt there was too much social isolation and too little community and human warmth, and you feel that moving to another country could help you meet that need (as it did for me). Alternatively, your mood may be very strongly dependent on the weather, and you may be living somewhere (as I was) where there is little sunlight for most of the year. In such a case, moving toward the equator is an obvious fix.

This is not to say that you can’t improve your chances of meeting your growth needs by moving. For example, escaping the strip malls of America and moving to an ancient Italian village will definitely boost the aesthetics of your life. However, as I discussed in the essay “The Beauty of Elsewhere, the Beauty of Home”, I believe that it is possible to learn to find beauty everywhere, if you work at it.

Research in social psychology suggests that some environments really do have a more positive impact on a person’s development than others, so where we live certainly can equip us, to some extent, with the tools we need to improve our life. An interesting question to which I don’t have an answer is whether this influence diminishes as we age.

Maybe you need a transplant

However, place is not everything. There is no guarantee that moving to a sunny and inexpensive place like the Yucatán or a vibrant and cosmopolitan place like Barcelona will grant you happiness. Why? Because of the other side of the coin.

Remember that (in our model) experiences are only partly physical; it is our own mental response to what happens that ultimately determines the tenor of the experience. I can move to Portugal and be thrilled by the lemons and the brilliant blue sky, or I can move to Portugal and be horrified that the public systems never seem to work. Of course, I can have both of these reactions, but which one will predominate? That depends entirely on what goes on inside my increasingly bald and sunburned head.

I am a very firm believer in working on oneself. This is something that is incredibly difficult to do—it is difficult even to know where to start. But there is no shortage of self-help literature, coaches, and gurus out there. I do not say this disparagingly—some of these are excellent. I would not be where I am today without the guidance of figures like Ram Dass, Eckhart Tolle, Alain de Botton, Martin Selligman, Brené Brown and David Richo. They have taught me a tremendous amount about understanding myself, seeing my place in the world, and taking responsibility for my own happiness. If I am doing well today, it is not primarily because I moved to Europe, but because I have done many years of difficult work to fix myself from the inside out.

In fact, having done this self-work is what enables me to live in Portugal and face with equanimity all of the fruitless appointments, disappearing workmen, non-existent buses, murderous calçadas, moldy walls, and freezing interiors that are the landscape of life here. I knew it would be like this, so I am OK with it. If I had thought that Portugal was just California with tax breaks, I would be suicidal by now.

I needed to move, but not everyone does. I am certain that many people have the wherewithal to change from the inside without changing where they are. It is all a question of what your deficiencies are and what kind of growth you aspire to.

My very strong suspicion is that few people require only a change of scenery. Most of us also need to work on ourselves, if we truly want to have a fulfilling life.

In sum, individuals are different and have different needs. Maybe what you need is to be transplanted to a new environment where you can grow and flourish. Or maybe what you need is a new liver—something to help you live, wherever you decide to do it. Medicine can give you a physical liver, if that is what you need, but only you can learn to live better on the inside. Either way, you will be left with some scars. The big, hard question is this: What is it that really needs fixing?

Those involved in the debate (according to

, at least) are , , , , , , , , and .If you like the combination of writing about living abroad and psychological theory, I recommend

, especially the series in which she goes into depth about my 10 questions to ask yourself before moving.If you are concerned about how to move abroad in an ethical way, you might want to check out

’s The Conscientious Emigrant.

Great essay, but naturally a social scientist will like any content that includes Maslow's updated hierarchy of needs. Gorgeous photos ttoo! I hope we get to meet and hang out some day, everything you say here resonates so strongly, I wrote a little about this myself when someone said to me, well it's much easier to do this (move abroad) with a partner, than being alone. I wasn't so sure about that.

Yes, it is easier, in some ways, to make this move with a partner without a doubt. But there are downfalls too, especially if you are financially tied together. You might feel trapped when the future does not look as bright as it once did. You might experience the terror of abandonment, managing those emotions alone without your lifelong friends and family support system nearby. I would tell each member of a couple, don’t come because you are jointly committed. Come because you yourself really want to do this above all things. Because you may find yourself alone here, the unthinkable, the unexpected could happen to your partner and/or relationship. When your world is turning upside down it’s important to be ready to like being alone with yourself right where you are.

This is an excellent post, and I really appreciate your in-depth exploration of this question. As someone who left in large part out of fear and anxiety (and rage) about racial hostility, with stark unaffordability (a $400 rent hike and the residue of a COVID layoff), leaving in 2022 saved our lives.

One point I would add: when one's environment causes a chronic amygdala hijack, it can be very difficult to "do the work" of self-help. And cruelly, that is when you need it most. In my case, I needed the space from the US to heal from it.

This paragraph really encapsulated this, and I want to tie this point to the way that gaining the equanimity necessary to deal with the challenges of moving to a new country, in some cases, could only be gained by moving there. "Here is what I suspect: Moving to another country makes the most sense when the needs you are struggling to meet are toward the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy—the deficiency needs. All refugees know this. If you are a trans person facing threats to your physical safety, or a woman facing challenges to your bodily autonomy, then moving to a safer environment could make sense. Similarly, people who are facing financial ruin because of the cost of healthcare where they live have a good reason to move to a place where healthcare is considered a right (i.e., a normal country). That said, greed is not a motivation that I can endorse; many people want to leave their country simply because they wish to avoid paying taxes. I see this as unfortunate, short-sighted, and unlikely to lead to happiness."

We can only be happy when we are healed, and it's very difficult to heal from a wound when bigoted, miserable people are chronically levying their hate at you. Like picking a scab.

I'm so grateful we left, and helping others - especially those on the front lines of fascist attack - trans and racially targeted people - to leave is the least I can do.