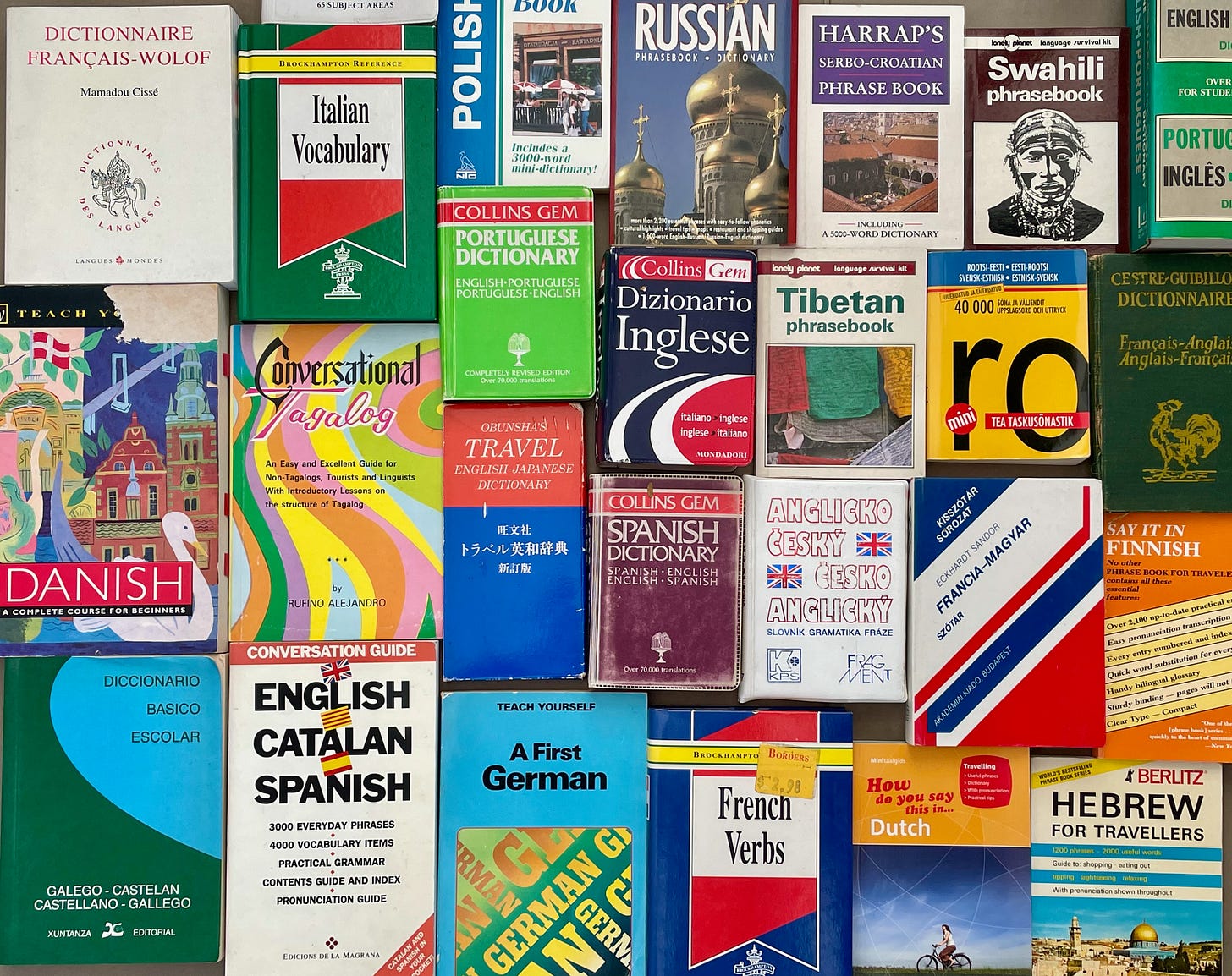

The Magic of Multilingualism

The benefits and brilliance of being bilingual

I love languages. As someone who has spent most of his life learning languages (to wildly varying degrees of accomplishment), and as someone who has spent over 25 years teaching languages (in various countries), and as someone with a PhD in linguistics (who worked as an academic for two decades), I have many thoughts on learning and speaking languages. What I hope to do in this piece is to portray some of the many and fascinating faces of multilingualism, and for those who may not really be convinced, the advantages of speaking more than one language.

What do I mean by multilingualism? Very simply, the ability to speak more than one language. We often use the word “bilingual” for someone who speaks two languages well, but many people speak more than that. So let’s just use “multilingual” as a general term for anyone who is not monolingual. The word “polyglot” is also used, but almost always boastfully, so I tend to avoid it.

People frequently ask me how many languages I speak, and I always find this stress-inducing. Our relationships to languages can vary tremendously. If we think of them as being equivalent to romantic relationships, I could say that I have been married four times, have had three serious relationships, and have had half a dozen flings. That is, there are four languages that I have put as much work into as a marriage, three that didn’t quite lead to the same level of commitment, and several where I knew it wasn’t really going anywhere, though it was fun at the time. This is a good analogy, because it suggests that languages are something that requires a great deal of time, effort, and attention—which is true.

The myriad manifestations of multilingualism

It is utterly fascinating to move through the world and see the different ways in which using multiple languages can play out. The scenario that is probably most familiar to anglophone Americans is using foreign languages while traveling: going on vacation to Mexico and using your high-school Spanish, for example. And that is a fine case of language use, but there are so many more. Here’s something to think about: There are multilingual individuals and there are multilingual contexts.

Diglossia

For example, there is the situation known as diglossia, in which people know two languages and use them both in daily life, but in different contexts. India is a good example; in addition to the dozens and dozens of languages spoken across the country, many people also speak English, which they use in formal, institutional settings, such as education, administration, and business.

However, Americans don’t have to go around the globe to find examples of diglossia. Consider all the Spanish-speaking communities around the country, in which friends and family members communicate with each other in Spanish but switch to English when they go to school, conduct business, go to the doctor, or get their driver’s license. These people have far more linguistic resources than their monolingual countrymen, so it is with great sadness that I see the use of Spanish being increasingly persecuted by the government.

Lingua franca

Obviously, nowadays the most commonly learned language on planet Earth is English. It’s not the language with the largest number of native speakers (that’s Mandarin, followed by Spanish), but it does have the largest number of non-native speakers, with an estimated total of 1.5 billion people using English around the globe. Interestingly, since only one-quarter of those people are actually native speakers of English, this represents a massive example of people using a lingua franca. This is the term used when two people communicate by means of a language that neither of them speaks natively.

There is a certain irony in the fact that lingua franca actually refers to French, which served this function more widely than English did a few centuries ago. So in a way, we are saying that the most widespread French language is English.

We see examples of English being used as a lingua franca in myriad contexts: French tourists in Japan using English to order their food; Iranian students getting a master’s degree in the Netherlands; even Swedes talking to Danes who speak a dialect that they just can’t understand. But the context that I find most fascinating, mystifying, and perplexing... is dating and relationships.

I have seen many cases of middle-aged German and Swedish men who have obviously gone to Thailand to find a bride and bring her back to Europe. Sometimes these couples communicate well, but sometimes I hear dialogues like “Beer. You want?” “Yes. How much cost?” “It cost five euro.” “Maybe one only.” And I think, what would it be like to have a life partner with whom one communicated in three-word sentences? But maybe it works for them. Not everybody writes on Substack. Yet.

I want to mention one case in particular. For several years during my time in Sweden, I went to a masseuse who was from China. She was a wonderful person who I adored. Linguistically, however... I am sure that she spoke Mandarin quite well, but I can attest that her Swedish and her English were both—how can I put this—existentially negligible. If language were furniture, her communication would be a couch made out of stones, cardboard and duct tape. Scheduling appointments with her was achieved using a combination of Swedish and English words and grammar—I’m not even sure she understood that they were two different languages—and having a conversation was impossible, at least while I was lying down and thus unable to gesture.

And yet this woman eventually married a Swede—someone I’m pretty sure doesn’t speak any Mandarin. I gave her a gift but didn’t attend the wedding, so I never got to witness her communication with her new husband. I have often wondered what their home life must be like. But she seems happy, so who am I to judge?

Code-switching

Surely one of the coolest manifestations of multilingualism is the use of two or more languages simultaneously—what is known as code-switching, or in a more extreme form, code-mixing.

Back when I was young and had lots of hair, I also had a Portuguese girlfriend, at least for a while. Her English was much better than my Portuguese, but I was gradually catching up to her. Not long before the relationship ended (see this piece), there was a period when we would engage in conversations—especially when tired—in which each of us would speak their native language, producing dialogues like this:

C: Como estás?

G: I’m pretty tired.

C: O que é que queres fazer para o jantar?

G: I don’t really feel like going out, but I don’t have much food. Could we cook at your place?

C: Não sei o que tenho em casa, mas podemos passar pelo supermercado. O que achas?

G: That sounds good. I kind of feel like chicken. Could you make that nice chicken dish with potatoes?

C: Leva bastante tempo. Acho melhor que façamos uma coisa rápida.

G: Right. And I’m pretty hungry, so fast sounds good. Maybe pasta?

etc.

While this is a fairly extreme example, simply having the ability to communicate in this way was liberating. Plus, I loved the looks we got on the subway.

In somewhat less extravagant forms, code-switching is a perfectly ordinary part of life in many countries. During my years in Sweden, I would jot down instances, especially from conversations overheard on the train or the bus. These were endlessly fascinating. Frequently, someone would be speaking Swedish and would suddenly produce a sentence in English. Here are two (unrelated) examples:

You’re mentioning the war.

By now I know my bladder.

In other cases, the switch would come within the sentence, but between clauses:

Det blir bara så där, slap in the face.

“It’s just like that, slap in the face”Oh my god! Så dramatisk.

“Oh my god! So dramatic!”

And then there are the ones with just one word in another language:

Alltså literally vad som helst.

“I mean, literally anything at all.”Ja men det är ju så obvious.

“But it’s so obvious, you know?”Och service-minded på ett trevligt sätt.

“And service-minded in a nice way.”

From my perspective, having the ability to do this—and crucially, having a community of fellow speakers who will understand us when we do—is one of the most delightful and enriching aspects of multilingualism. I actually have quite a bit to say about the benefits of multilingualism, so let’s turn to that, vad säger du?

The burgeoning benefits of being bilingual

As I see it, there are three main types of benefits that come from speaking more than one language: functional, social, and personal. I will address these in separate sections in the hope that you won’t notice how long this text is getting.

Functional benefits

Perhaps one of the most obvious things that become possible when you learn another language is that you can understand texts in that language: books, newspapers, magazines, websites, songs, films, television, and all of the signs and documents that one encounters when one travels. Not all of this will have been translated to your native language—and depending on what languages we are talking about, almost none of it may be. Everyone reading this essay who did not grow up speaking English is an example of someone reaping this reward. (Not wanting to overvalue my own work, of course, but hey.) If you were from Italy and learned to speak French, you would have doubled the amount of culture to which you had access. That’s not bad.

Obviously, knowing other languages aids us in traveling. The experiences one can have in another country are so much richer if one speaks the language. A case in point: While writing the previous paragraph, sitting in the cafe at the local library, I became embroiled in a discussion between the proprietor Sonia, who is an enchanting woman with a daughter who is a political scientist and lives in the Czech Republic—so more multilingualism there, but let’s not get completely derailed—and another woman, about whether Coca-Cola tastes different in different countries, and if so, why.1 The other woman (who has no relevant credentials that I am aware of) claimed that the ingredients are all the same apart from the water, which is local. And therefore, the taste of the soft drink is dependent on the taste of the water where the factory is located. I asked Sonia where Coca-Cola is produced in Portugal, and she quite rightly pointed out that I was sitting at a computer and could Google it. It turns out that the factory is located in Azeitão, which seems ironic, as this is also one of the main wine-producing towns near Lisbon. And because I know Portuguese, now I know all this. And because you know me, you know it too. So there’s one example.

And if knowing the local language makes travel to a country easier, it makes living in the country exponentially more so. I would frankly be terrified to move to a country where I didn’t speak the language, although I know many people who have done so and more or less survived. If you move to a new country and learn the local language, that opens up possibilities for employment or other work. I know a guy from California who came to Lisbon and opened a restaurant, and his Portuguese is getting better every day. And this, naturally, leads to social benefits as well. So let’s talk about that.

Social benefits

Speaking multiple languages creates a widening pool of potential social contacts. While it’s true that many people around the world speak English, most don’t. And many people who are capable of using English for business are not keen to use it for friendship. Let’s say that you, like me, were to move to Portugal and wanted to make friends. You would have three options: (a) find other foreigners who speak English (or whatever your native language might be), (b) find Portuguese people who are willing to socialize in English, and (c) learn to speak Portuguese, which—at least in theory—unlocks the rest of the population. My perception is that category (b) is difficult, as few Portuguese, at least over the age of 30, are interested in forming friendships in English. Category (c) is certainly difficult in the sense that learning a language is no walk in the park, and it doesn’t guarantee anything—but it gives you about ten million more candidates among whom to look for friends.

And that brings us back to dating. If you are looking for a new partner in a new country, speaking the language opens up a vastly greater pool of candidates. And of course, being in a relationship with someone from the country is one of the best ways to become acclimated to and assimilated into the culture.

But even setting aside all questions of love and friendship, learning the language of a place, as I argued in “How to Be a Good Immigrant”, is central to developing an understanding of that place, as it is a window into the society and its culture. The social benefits that accrue from really knowing the country are enormous.

Personal benefits

Finally, we come to the more intangible personal benefits of multilingualism. To convey these, let me give another example from my own life.

For a couple of years in Sweden, I was in a relationship with a woman from Mexico who had two children with her Italian ex-husband. The daughters, who I adored, spoke four languages. Even though my Italian wasn’t very good at the time, I still had the option of communicating with these girls in Swedish, Spanish, or English. A situation such as this is so intensely rich, with such great opportunities for flexibility and with such delightful potential for playfulness, that I was secretly envious of the girls for the advantages they were growing up with without ever reflecting on it.

Imagine being able to have a sense of identity as a Swedish speaker and as an English speaker and as a Spanish speaker and as an Italian speaker! There are so many more doors open to people like these girls by virtue of growing up with several languages—and thus access to several cultures—than I ever could have dreamt of during my own monolingual childhood. While I never really wanted children of my own, I do sometimes dream ruefully of the gifts that I would have liked to give my children. Multilingualism is one of the primary ones.

Something that any true polyglot will tell you is that the more languages you know, the easier it becomes to learn new ones. The reason for this is simple. As I explained in “Loving Learning Languages”, if we think of learning a language as a journey to a destination, the more languages you already know, the more starting points you have for your journey, so the shorter it can potentially be. Knowing any one of the Romance languages, for example, makes it much easier to learn another one.

Another personal benefit of speaking multiple languages is the mental stimulation that it produces. The jury is apparently still out on whether multilingualism prevents Alzheimer’s, but there is no doubt that it is a good cognitive workout, which not only increases one’s mental agility but can also lead to intensely delightful experiences. Within the family I just described, I would jot down sentences that seemed to be extreme or playful examples of code-mixing, such as the following:

Entonces podemos parlare italienska.

“Then we can speak Italian.”

[Note that words 1-2 are in Spanish, word 3 is in Italian, and word 4 is in Swedish!]Yo växlo mellan los språk.

“I switch between languages.”

[Note that words 1 and 4 are in Spanish, words 3 and 5 are in Swedish, and word 2 is a Swedish verb with a Spanish inflection added.]No lämno nada tillbaka.

“I don’t return anything.” [as in a library book]

[Note that words 1 and 3 are in Spanish, word 4 is in Swedish, and word 2, again, is a Swedish verb with a Spanish inflection. Note also that grammatically, this is a sentence with the double negation that Spanish (but not Swedish) allows, and a phrasal verb, something that exists in Swedish but not in Spanish.

These are masterpieces of the blending of languages, and as such, are fantastic expressions of individual creativity. Please note that these speakers (who in some cases might have been me—I didn’t write down who said what) are perfectly capable of constructing “proper” grammatical sentences in any of these languages, in the same way that Picasso was perfectly capable of painting a pigeon in a realistic fashion. But what fun to be so creative, so generative—and to have others get it! This is where the personal benefits of multilingualism meet the social benefits, because co-creating using linguistic resources is something that produces bonds between people, in addition to producing joy.

I hope that this rather lengthy tour of multilingualism and its benefits has left you itching to fire up an app or enroll in a course. As I said in “How to Be a Good Immigrant”, I have never heard anyone complain that the time they spent learning a language was a waste. Is it easy to learn a new language? No, certainly not. But the potential benefits can be life-changing.

If you would like to read some related essays, I would recommend these:

I apologize for the length and complexity of this sentence. I also apologize to the world, as an American, for Coca-Cola.

This was an inspiring and entertaining read. I'm not a linguist but I do appreciate multilingualism and have understood, from an early age, the opportunities that languages could afford me. Learning foreign languages seemed to come to me rather easily, and I relished in the experience and the outcome.

As an immigrant from China to Hong Kong, I learned to speak Cantonese by watching dubbed American black-and-white TV series. At home, my mom spoke the Hangzhou dialect, my dad spoke Mandarin with an Indonesian accent, brother and I spoke the "proper" Mandarin at school while Cantonese outside of class and at home with out parents. Somehow, we made all these dialects and accents work without too much confusion. Oh, and then there was English, of course, the official language of the colonizers. Brother and I did not speak it in everyday life, but we had to learn it in school. Code-switching was normal for us. You would often here an English word here and there within a Chinese sentence. For my mom, who struggled with learning the local Cantonese, often combined (and still does) Mandarin, Hangzhouese and Cantonese in a single sentence. The result is quite hilarious.

In secondary school, I became exposed to the existence of French. Upper-class and non-Chinese girls in my school got the option to learn French instead of Chinese. I was quite jealous. When the dream of studying in France was ignited in me, I decided to learn French outside of school. Since then, I've learned a third language and it became my favorite. I felt free using French to express emotions that I wasn't able to express in either Chinese or English.

Fast forward many many years, I married a Swedish guy who spoke 5 languages. It was fascinating to me, and intellectually stimulating. We often spoke English, Swedish (after I've learned it) and French with each other, and we enjoyed many films in these languages. One of my proud accomplishments is to have watched and understood most of Igmar Bergman's movies in Swedish without subtitles.

Sadly, my ex-husband never learned my language even though we lived in Hong Kong for 10 years, claiming it was too difficult. We did use Swedish as our secret language when we were out in the public, to avoid people eardropping on us.

In terms of your puzzlement about married couples who communicate with three words, well, I have my own theory. I've seen it between Western men and Thai women. In fact, my ex-partner, who cheated on me with many Thai women, seemed to be rather satisfied with the kind of language exchange you described. My therapist at the time suggested that because my ex didn't like to be known for who he really was, he would rather engage with women who would never get to really know him (unlike me). Transactional relationships would work best for people like him. Well, that made a lot of sense to me, and perhaps can explain why marriages between the Germans or Swedes and the Thai's work, despite minimal communication. By the way, this ex-partner also never learned my language but was enthusiastic in learning Thai while living with me. Imagine how that made me feel.

I saw the cover of a book comparing the grammar of different Romance languages. I wonder if it's still available and if so, where can I get it. I'm always looking to expand my language skills and since I can speak French, I figure it wouldn't be too difficult to learn how to speak other Romance languages.

Well, when it comes to the subject of language, I can go on and on, but I need to sleep. So I will stop here. Thank you for opening my "lingua floodgate"!

Absolutely! Intercultural communication, combined with cultural awareness, is essential for effective collaboration. In my experience, especially in Southern Europe, this is often overlooked under the assumption that there are cultural similarities. But differences do exist—and language is a powerful mirror of those differences.