Probably the most controversial thing I wrote in my recent post, “Are You One of the Few Americans Who Really Could Move to Europe?”, was that “if you move to a country with a different national language, and you do not learn that language, you will never have a satisfying life in that country.” The problem with this statement is that whether or not it is true really depends on what you find satisfying. Rather than discussing that, my goal here is to offer some reasons for learning languages and some suggestions for doing so successfully.

Why learn languages?

What do we gain when we learn to speak a new language? For one thing, we gain mental agility. Learning anything complex wakes us up and makes us feel more alive. And learning languages may reduce the risk of developing dementia. You might feel like you’re too old to learn a language, but I bet you also feel like you’re too young for dementia.

Of course, the main thing learning languages does is allow us to communicate with more people—but this can take many forms. In some cases, it can enable us to communicate better with those we already know. Millions of people around the world are married to someone with a different native language, or have parents or grandparents with a different native language.

In other cases, learning a language enables us to communicate with native speakers we meet when we travel, as when an American goes to France and tries to speak French (which they really will appreciate!). In addition, many languages (like English, French, Russian, Swahili, Mandarin, etc.) can also serve as a lingua franca—that is, as a third language that allows people to communicate who otherwise couldn’t. This is the case when a German visits Croatia and gets by using English.

But also: Taking language courses introduces us to other learners. I got a message the other day from a Finn I became friends with when we were both learning German thirty years ago. When you are new in a country, language classes are an excellent place to make friends.

And for those who really get into it, becoming a language teacher can open up jobs all over the world. A good friend of mine lives in Iowa but teaches French at university (sorry, at a college—got to keep my English American) and has now published seven French textbooks.

Finally, when we learn a new language, it makes available to us new slices of reality. I remember the thrill I felt when I was able to start reading Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetry in German, or Henning Mankell’s mystery novels in Swedish. For a time, I actually entertained the idea of moving to the Czech Republic just to learn Czech, just to be able to read Milan Kundera in the original. But I didn’t, and I never will, which just intensifies the incredible lightness...

But if literature isn’t your thing, imagine the thrill you would feel the first time you went to a restaurant in Istanbul and successfully ordered lunch in Turkish. Imagine traveling across China and not having to rely on finding English speakers. Imagine—for some of you—being able to read the letters that your grandmother used to send back to the Old World. I was once hired by an American woman of Spanish descent who had found all of her grandparents’ love letters and wanted them translated to English so that she could understand the world they had come from and the life they had lived.

Since we experience the world through language, learning a language gives us a new portal through which to approach the world. Isn’t that pretty cool?

My life as a language learner

My first love was Spanish. I studied it from the age of twelve, and, discovering that (a) I was pretty good at it, and (b) it felt amazing, I got hooked. (I sometimes wonder what my teacher Señora Giles would think if she could see what I’ve done with my life.) I eventually went on to study Spanish and then linguistics, though there were embarrassing excursions into other fields that I might talk about some other time. To date, I have put some amount of effort into studying at least ten languages, to very varying degrees of success. There are only four in which I am truly comfortable (English, Swedish, Spanish, and Portuguese); using the others is always accompanied by a certain amount of perspiration.

I’m telling you this because I want to compare two different degrees of accomplishment in language learning. When I speak Italian, for example, I feel really great when I get through a whole encounter with the sense that I understood everything, and didn’t confuse the words for “hat” and “coat”, for example. But, whenever I’m in Italy, there is, all too often, that feeling of “Oh shit, here comes someone—I’m going to have to speak Italian!” Being at this level feels really good—but only some of the time.

Here in Portugal, after more than a year of excavating my rusty Portuguese, I am enjoying a markedly different experience. People are continually surprised that such an obviously foreign-looking guy speaks Portuguese with (almost) no hesitation. In the past month, I have heard the words excelente, fantástico, and espectacular applied to my Portuguese—which is not accurate at all, but means that I speak much better than someone who looks like me is expected to speak. And that, understandably, boosts the confidence of this normally rather timid North American enough that he has started to integrate into the society, little by little. I now have friends who don’t really speak English, so I feel like I’m over the hump. And that feeling is thrilling.

Below, I’ll give you some suggestions for getting over that hump. Just stick with me (and no, there’s no paywall).

English is easy, right?

Let’s talk for a moment about “hard languages” and “easy languages”. Many years ago, I had a student in Germany who would say, quite arrogantly, “English langvage, easy langvage!” Yeah, great... thanks, Udo. 🙄

I will now pull out my tattered and creased Linguist License and wave it at you while I proclaim the following: There is no such thing as an “easy language” or a “hard language”. Think of a learning a language as getting to a destination. How long it will take you to get there depends on where your starting point is. Learning Russian will be a lot harder if you only speak English than it will be if you’re a Polish speaker. Similarly, learning French is vastly easier if you are Spanish than if you are Korean. In sum, if the language you are learning is fairly similar to the one(s) you already know, learning it will be easier.

And here’s the cool part: Did you see that little (s) in the previous sentence? The more languages you know, the more starting points you have to begin from. As you study more languages, fewer concepts will be new to you when you encounter them. Linguists starting to learn a new language can say things like: “Oh, so Slovene has singular, plural, and dual? Far out!” And then carry on.

But what about talent? I hear way too many people claim that they can’t learn languages because they don’t have the talent. Frankly, I reject this argument. Are some people better at learning languages than others? I would say that yes, that seems to be the case. But nobody is unable to learn new languages. It’s a question of... well, I’ll talk about that in a moment.

First, let me point out that the area in which individual talent seems to be most significant is pronunciation. People vary massively in how well they learn the sounds of a new language. My professional opinion on this is that this is because we almost never teach pronunciation effectively. And so, some will get it (through sheer luck/innate talent) and some won’t.

I remember once, many years ago, when I was teaching Spanish at Boston University. I shared an office with an elderly lady who taught Italian. One day, she had a student in, who had missed some classes and was trying to catch up. They were working on the article gli, as in gli studenti (“the students”). The student kept saying it wrong (“Li!”) and the teacher kept saying, “No no no! Gli!” This happened about five times, before I lost patience, spun around, and seethed, “Tell her to use the middle of her tongue, not the tip!” The teacher looked at me with alarm, but said, “OK, do what he said!” The student said, “Gli!”, and the teacher shouted, “Perfect!”

So if you are lucky, you will find a teacher who actually knows how to teach pronunciation. Or maybe you are Cher and have an incredibly musical ear, so you can apply it to your language learning. (If you are Cher, would you please direct message me? 🙏)

Three key elements

Let’s talk about three key elements of language learning that can make all the difference. These are input, motivation, and practice.

In linguistics, we talk a lot about linguistic input. This means “what you hear or read”. As you can probably imagine, it’s hard to learn a language that you’ve never heard. But at the same time, hearing a language is no guarantee that you will learn it. The key seems to be to get input that you mostly understand. If I turned on the TV to a Chinese channel, I wouldn’t learn anything at all, since it would be completely incomprehensible to me. But if I put on an Italian program, I could possibly follow it—and along the way, I might learn a few new words. This is what you are aiming for. To learn a language, you want to expose yourself to input that you mostly understand, but that contains new things that help you to develop. And you need to do this a lot.

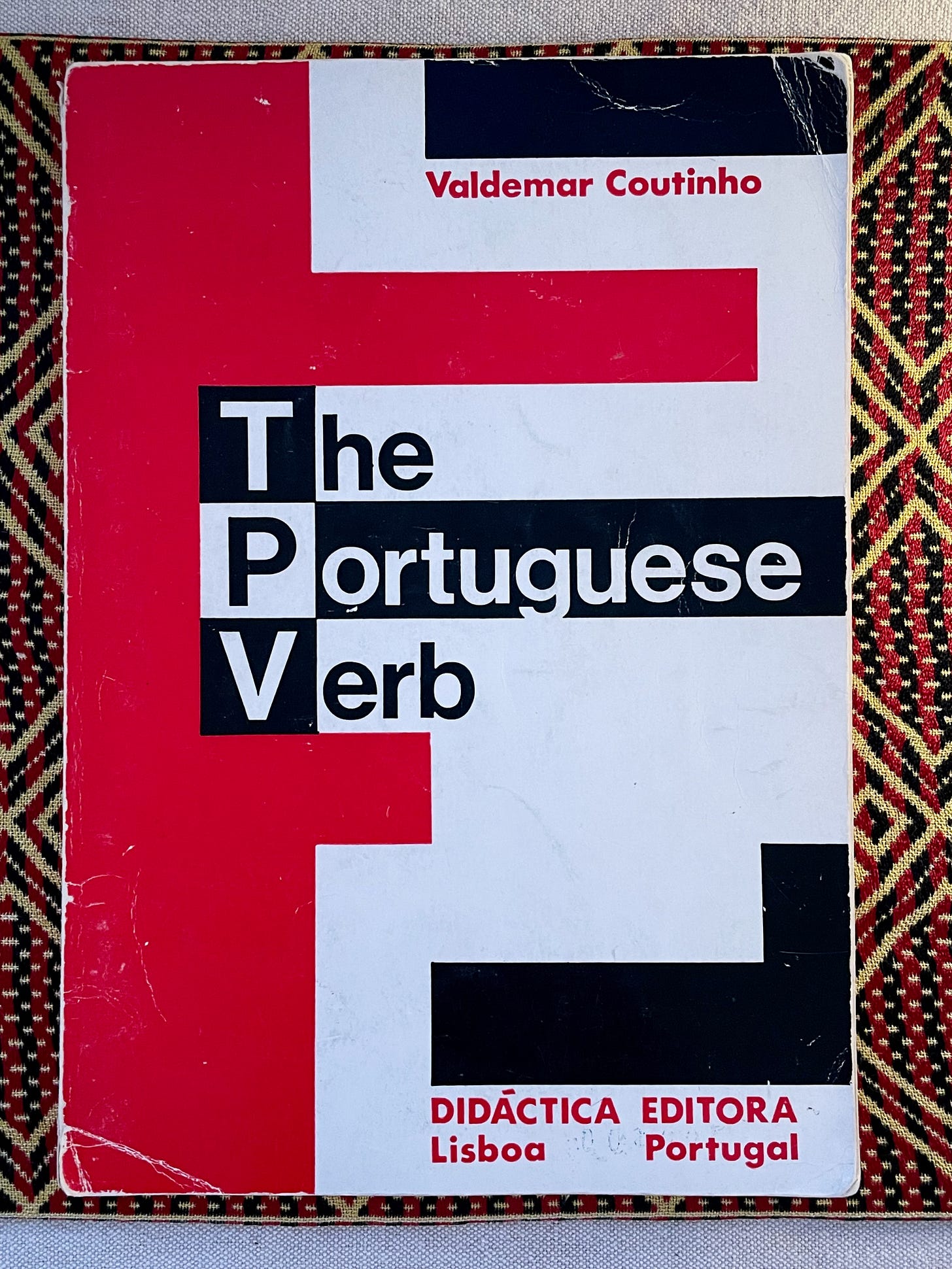

As an aside, the worst thing about language textbooks, in my humble opinion, is that, in trying to present material that beginning learners will mostly understand, they present stuff that an adult finds wildly boring, or irrelevant. I remember using a Spanish textbook that talked about going to a zoo. That was the last thing I wanted to use my Spanish for!

So: input—the level, the quality, and the quantity—is very important. So is motivation. If I were spending two weeks in Ethiopia, I would not really care whether I learned any Amharic. But if I were a diplomat stationed in Addis Ababa, I bet that I would care. And if I wanted to open a shop there, I definitely would. The fact is that language learning is such a massive task that only the people who really want to learn are likely to do so. In this sense, it’s like learning to play an instrument. That said, some people, especially linguists, do decide to learn languages for reasons that others might find surprising.

Obviously, if you are considering relocating to a new country, you have a spectacular motivation to learn a new language.

The third element of language learning that I want to highlight is practice. As with any complex skill, you are not going to learn it through osmosis. Imagine that you wanted to learn to play the oboe. Going to lots of classical concerts in which the oboe was played might be good for your motivation, but it wouldn’t help you learn to actually play the instrument. For that, you need both to want to play it and to practice playing it. Language is much the same. To learn to talk to people, you have to get out there and talk to people.

But unlike with very poor oboe playing, most people will be very happy with your attempts to speak their language, and will be supportive. This is important, because it feeds back into your motivation.

Three tips for language learning

I do not have any kind of monopoly on the language-learning market. But I have worked as a language teacher for over twenty-five years, and I have learned a few languages—to the point where I can co-habit or have relationships with people in them—so I can give you some tips for learning a new language successfully. Here are three.

Spaced repetition

A sad fact about the human brain that becomes clearer to me with every passing year is that we do not remember everything. In fact, studies show that, failing any sort of intervention, within a week we will have forgotten 90% of what we learned today. This is depressing. And yet, there is a way of combatting this problem. It is called spaced repetition. Studies (starting with Ebbinghaus, 140 years ago) have shown that the key to remembering something permanently is to review it at increasingly long intervals. If I tell you right now that almôndega means “meatball” in Portuguese (and not “customs”), you probably won’t remember it tomorrow. But if you review that piece of information in 10 minutes, and then again in 1 hour, and then after one day, and then after one week, and then after one month... you will have achieved the state known as permanent meatball.

Note: I have just made this term up. It is definitely not an accepted term in linguistics. Yet.

Therefore, to build your vocabulary, it is useful to use a tool that has the concept of spaced repetition built in. I like a free tool called Anki (it’s free on your computer, at least), but there are others out there.

The general point is that if you want to really remember a piece of information (linguistic or other), keep reviewing it, at longer and longer intervals, until you no longer need to.

Gamification

I suspect that many people born before about 1980 don’t really see the point of computer games, or worse, see them as a waste of time. But one thing that has become increasingly clear is that people like games. Whether it be gambling, old-fashioned card games, massively multiplayer online games, or immersive first-person games, people love a good game. It appeals to many aspects of our psychology.

Increasingly, this insight is being baked into platforms for language learning. Let me use the example of Duolingo, a platform that has a mind-boggling 100 million monthly active users. Duolingo claims that “there are more people learning languages on Duolingo in the US than there are people learning foreign languages in the entire US public school system.”

Now, some people love Duolingo, and some people hate it. I am both of those people. I have been using it for a few years and currently have an impressive “streak” in learning Italian of 1067 consecutive days—since before I quit my life in 2022.

The problem with Duolingo is that it teaches language implicitly, not explicitly—you are never presented with a rule or a generalization. This is maddening to linguists like me, who (as I mentioned above) can save lots of time with a more top-down approach. But most people aren’t linguists, and most people seem to hate grammar rules. (Click “Like” on this post if you hate grammar!) I see why Duolingo is attractive to them.

So why is it attractive to me? It’s that damn streak. I don’t want to break it. Duolingo uses all sorts of techniques to make us feel that we are “winning”: by appealing to our competitive nature, our desire to advance and not fall behind, our love of winning awards, and our desire to have a “perfect record”.

All of this does not necessarily make for good pedagogy, but it keeps people motivated to continue—thereby overcoming one of the biggest challenges language teachers face. Oh, and Duolingo also makes use of spaced repetition to help you learn things.

Reading the right books

My biggest breakthrough in language learning was when I realized I was ready to take the plunge and start reading books in the target language (which is what we call the language we are learning). To move from language-instruction contexts and occasional service encounters to actually using the language in the way that native speakers use it—to read—is like stepping out of the pool and going snorkeling in the sea over a coral reef.

Teaching people to read is one of the primary goals of every nation’s educational system, because reading is how knowledge and culture are communicated across time. I think we take for granted how amazing it is that we can pick up a play written by some guy named Bill four hundred years ago and suddenly find ourselves in Renaissance Venice.

Now, you may have the advantage of being a native speaker of English, which is the language with the largest number of published books. But there are many, many other books that were written in many other languages—and, believe it or not, not all of them have been translated to English. Plus, I can attest that reading any work of fiction—and especially poetry—in the original is a vastly different experience from reading it in translation.

So reading in the target language is our goal. However, we need to start in the right way. When I was a college student studying Spanish, I was forced to read very long, very difficult texts, such as modernist works in stream-of-consciousness, at a very fast pace. I took one course in which we had to read and discuss one novel per week, but I had four other courses, too! This was too hard for me, and I found it very stressful. Reading things that are too difficult does not make for a very satisfactory educational experience.

Remember what I said earlier about input? The goal is to take in language that you mostly understand. So you should transition to reading books when you are able to actually read one and make sense of it. Here are three tips for making this work:

First, choose to read a book in the target language that you have already read in English or another language—and preferably, one that you really like! If you are familiar with the story, you will be able to follow it much more easily in a new language.

Second, choose a genre that lends itself to easy comprehension. My favorite is police procedural mysteries. Why? Because they are quite repetitive, have a relatively restricted vocabulary, are very dialogue-focused, and are exciting—so you actually want to keep reading.

Third, read with a pencil, a dictionary, and a notebook so that you can mark new words, look them up, and write them down for later study (remember spaced repetition? See how I’m mentioning it again? 😎). Here is my suggestion for how to deal with new words. Consider these four categories:

words whose meaning you can infer from the context

words whose meaning you can infer because they are similar to words in another language

words whose meaning you can’t infer but that don’t seem very important

words whose meaning you can’t infer and that seem central to understanding the text

My policy is to always look up words of type 4 when I come across them, because that helps me follow the story. I might underline words of all of the other types if they seem interesting, and then come back to them later. In this way, my attention is not constantly shifting between the book and the dictionary. Wouldn’t want to let that murderer escape!

I discovered all this back when I was learning Swedish and decided one day to finally take the plunge and start reading books in Swedish. I chose Henning Mankell’s detective series about Kurt Wallander, which I had already read in English. I found that my familiarity with the books and the characteristics of the genre made for a very positive reading experience. And my vocabulary exploded!

And in fact, more recently, while I was living in Italy, I came upon some Henning Mankell books in the bookstore, and I thought, “What the heck!” I bought them and read them in Italian—the very same books I had already read in English and Swedish. It was great, and worked wonders for my Italian, though I have to admit that sometimes I would get cognitive dissonance from hearing all of these dour Swedish policemen standing around in quaint little Ystad in Skåne, arguing about a crime scene—in Italian.

So those are some things I would recommend thinking about if you are considering taking on a new language. If you do, I applaud you, and I hope it goes well. I can’t imagine ever thinking that time spent learning a language was not time well spent.

A voluminously illuminating post. In my case, the primary factor in my failure to become multi-lingual was psychological. Liza alludes to this point in her comment about letting go of one's ego. When I was learning French in school, I did well enough in writing and reading comprehension, but I would flail in conversational exercises. The moment when I heard something that I didn't fully understand, and when I had a thought that I couldn't fully convey in the meager French that was at my disposal, I would freeze up. Some combination of general anxiety and my particular sort of perfectionism kept me from ever approaching fluency. A related barrier involves acutely feeling the gap between how fluently I could convey a thought in English and how feckless and speechless I would be in trying to convey the thought in French (or another non-native language). In sum, I posit that a key ingredient in language acquisition—one that you could fold into the category of "motivation"—is a willingness to fail, to sound and feel stupid, and to speak at a grade-school level even as your mind chugs along at a grad-school level. (Par exemple: You need to accept that it will take much time and effort before you can finesse the use of terms like "grade" and "grad," as in the preceding sentence.)

Also, besides reading a book you already know, an audiobook of the same can be great. With French I started on Harry Potter that I set at a slower speed and listened while walking the dog. Which translates into 20-30 minutes a day. About a third through the first book I was able to put it on normal speed and felt like a genius. I do know plenty of odd words now, wand, cauldron, a dungeon cell etc that I never use (lol) but it has been very helpful.