Welcome! This week we return to the topic of migration with another two-part series.1 This series, The Good Migrant, consists of this essay, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Foreigner”, and “How to Be a Good Immigrant”, which is now out as well. Both of these will remain freely available, though I greatly appreciate any support from paid subscriptions.

I am writing this series because at this surreal moment in history, a rapidly increasing number of Americans are talking about “moving to France”, “moving to Mexico”, “moving to Canada”, etc. The point that I wish to make is that this is a completely different enterprise from “moving to Phoenix” or “moving to Seattle”. Moving abroad means emigrating from one country and immigrating to another. Thus, I want to talk not about the mechanics of moving but rather about the concept of migration.

Since there is so much history to this topic, so much happening now, and so much uncertainty about the future, I am structuring this essay into Past, Present, and Future. Ready? Let’s go.

Past

For millennia, people have been leaving their home and seeking a new one elsewhere. I will use the term “migrant” for such people, because it applies broadly; the same person can be called both an “emigrant” from the perspective of the country they are leaving and an “immigrant” from the perspective of the country they are entering, but “migrant” covers both perspectives.

There are many existing classifications of types of migrants.2 What I would like to do here is integrate these a bit and highlight four important dimensions of migration:

Purpose: why people move

Agency: whether they do it freely

Resources: whether they have little money or lots of it

Time: whether they see the move as temporary, cyclical, or permanent

Let me say a bit about purpose. People can choose to migrate for different classes of reasons: humanitarian, family, economic, study, and lifestyle. Humanitarian reasons include fleeing disaster, war, and persecution; we call anyone in this situation a refugee (and once they officially seek asylum, an asylum-seeker). Of course, families try to stay together as much as possible, so many immigrants attempt to bring their family members with them. Economic reasons for migration take many forms: cyclical migrant labor, moving for career opportunities, short-term placement by a multinational organization, even prospecting for gold! Also, many young people choose to study in another country; this is facilitated by means like the F-1 Visa to the USA and the Erasmus system in Europe.

That leaves “lifestyle” migrants. This is a term applied to those who simply wish to have a more comfortable life, and covers the vast majority of Americans who move to Mexico, France, Italy, or somewhere else where there is sun, a pleasant lifestyle, and a reduced cost of living. I fall into this category myself, since I recently moved from Sweden to Portugal simply because I prefer to live here.

The dimensions agency, resources, and time are fairly self-explanatory. When we add them all together, we see how many different types of migrants there can be. Here are some examples just from the European context:

A family from Ukraine who arrive in Germany fleeing the war

A Polish family moving back to Poland from the UK post-Brexit

Migrant laborers from Bangladesh arriving in Portugal every summer to pick vegetables

UN employees sent to Geneva to work for a certain period

Retired Brits who spend half of the year in a holiday home in France

Digital nomads who spend three months in one country and then move on

Note that I have not said anything about the legal status of any of these migrants. That is a separate consideration that is handled differently by different countries. This is a very important point to which we will return: Each country has the right (within the bounds of international treaties and EU law) to accept or turn away migrants of different types, and to develop its own procedures for granting them legal status. And this brings us to the importance of how we talk about migrants.

The words we use

Donald Trump rose to power in the United States by demonizing immigrants. This was a major part of his platform both in 2016 and in 2024, and it was highly successful. As is always the case with xenophobia and hate speech, his method was to try to dehumanize a large group of people in the US, the ones he termed “illegals”. He referred to these people as “animals” who were “infesting” the country.

But here’s the problem: “illegal immigrant” is not a type of person. Being illegal is simply a status. If Melania’s green card lapsed, I doubt Trump would start calling her an “animal”. This talk of legal status is really just a thin veil drawn over racist propaganda. Recently the Department of Homeland Security’s social media account actually used the term “dirtbags” to refer to a group of immigrants (see this excellent commentary on the Trump administration’s war on dignity, at The Long Memo).

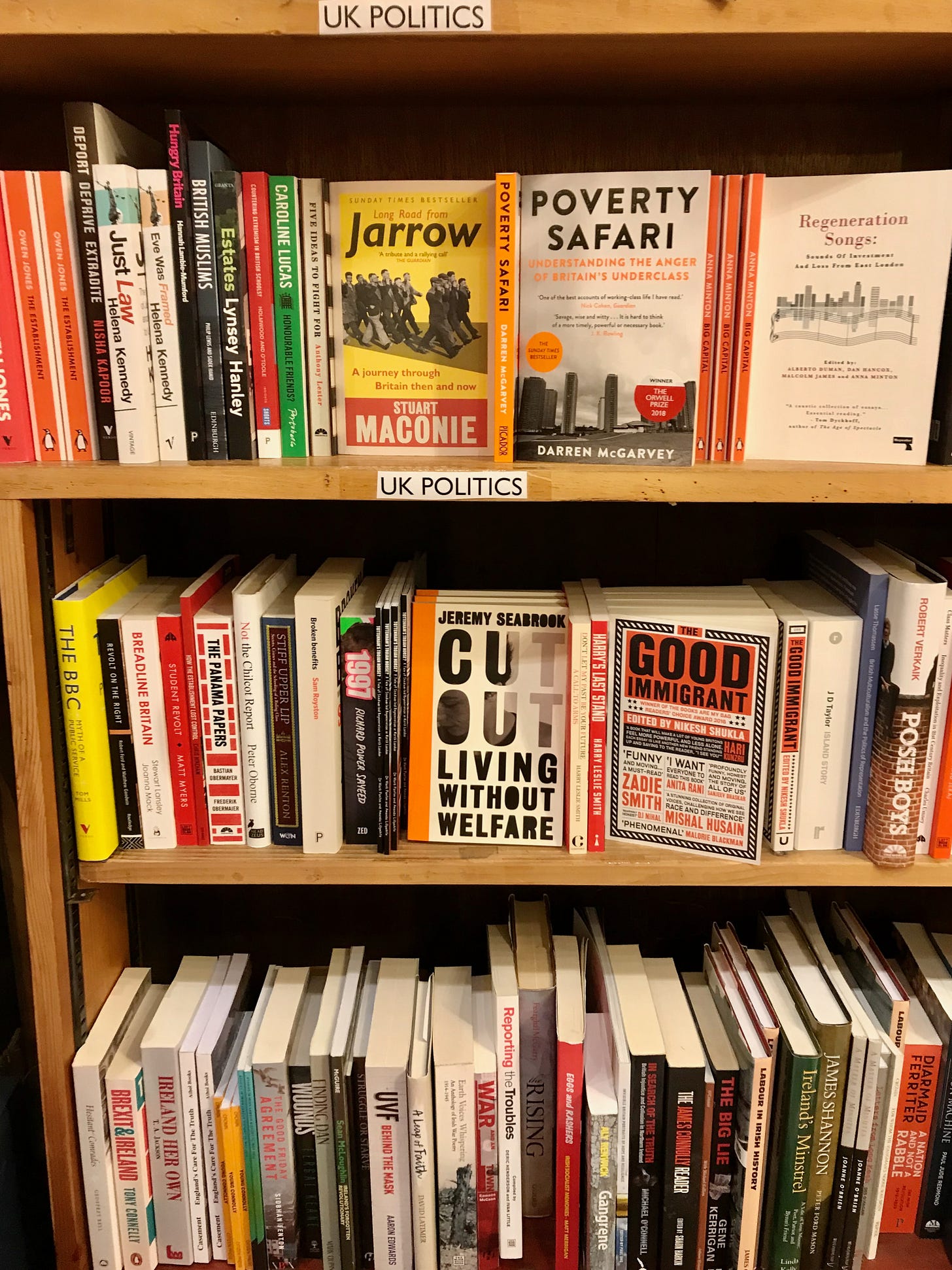

So yes, it matters which words we use to talk about migrants. In the US, the very word “migrant” is often associated with low-income seasonal workers. For this reason, many people of means prefer to call themselves “expats” when they move abroad. But this word also has its problems; many people find it objectionable, precisely because it is exclusionary. “Expats” are overwhelmingly white, wealthy, from English-speaking countries, and disinclined to mix with the locals. As such, the term tends to generate resentment.

The term “digital nomad” has also started to develop negative connotations in countries where such high-income, low-integration migrants tend to congregate. Certainly, here in Lisbon, the general feeling towards digital nomads is ambivalent at best, and outright hostile at worst. I will say more below about such resentments.

Occasionally I hear someone self-describe as a “global citizen” or “citizen of the world”. This, in my view, is also problematic, for two reasons. First, it suggests someone who is both in love with their own privilege and blind to how they are flaunting it in front of others. Second, it is wildly inaccurate. There is simply no such thing as a global passport. To be a citizen, you must pledge your allegiance to a particular country and abide by its laws while enjoying the associated benefits, such as travel. The European Union is the closest thing we have at present to an international citizenry, but when it comes down to it, one is not a European citizen, one is a citizen of a particular EU member state. And as the UK has shown us, this membership is not guaranteed to be stable. (Why, Britain, why?)

You may be wondering how I refer to myself, then. I will answer honestly. I am a citizen of both the USA and Sweden, and an immigrant in Portugal. I sometimes use the term “expat”, as there is a so-called “expat community” here that I have some contact with. But I would never use that word when talking to Portuguese people, as it would essentially mean placing a wall between myself and them. Assuming that I stay here in Portugal (that is my goal, but life happens, I’ve noticed), I hope one day to become a Portuguese citizen. Why? Partly so that I can vote and thus have a say about how my new homeland is governed, and partly because I want to show that I am committed to making this place my home.

Present

This is a strange time in history. Since the end of the Cold War, we have seen increasing instability around the world, as wars have broken out, financial markets have crashed, and the climate has changed, all while the global population has mushroomed. At present, over 4% of the world’s population—roughly equivalent to the population of the USA—has migrated to another country or is internally displaced.3 There are countries here in Europe such as Germany, Italy and Portugal that have seen an increase in population only thanks to immigration, without which they would be shrinking.

One of the reactions to all of the instability in the world is a swing back toward right-wing, populist, and even authoritarian regimes, which offer the populace promises of comfort and control in unsettling times. This has been happening in many countries, and now it is happening with terrifying speed in the United States.

A common theme to all of the right-wing, nationalistic movements that I am aware of is the demonization of immigrants and minorities, who make a convenient scapegoat for all of the problems plaguing a nation. I have already mentioned Trump’s attempts to dehumanize migrants who had come to the US looking for safety and economic prosperity, but it is significant that the Trump regime is now turning its attention toward other classes of migrants.

As you are probably aware, the US government has recently begun arresting foreign students who are in the United States with perfectly valid legal status and expelling them from the country.4 Who have they targeted? Protesters opposing Israel’s attacks on Gaza. This is being done under the guise of cracking down on anti-semitism, but let’s be honest: This is not really about Israel, it is about freedom of speech. Trump wants to quash any protest coming from the left, and he is using high-profile universities as an example to send a warning to liberals everywhere. But the fact that foreigners who are legally residing in the US are being expelled or imprisoned is a threat to the international order.

Of course, it isn’t only in the US that alarming things are happening. For example, in Italy, the right-wing government has recently been trying to change the laws that grant nationality, in an apparently unconstitutional attempt to revoke the citizenship of certain groups. Whether this will succeed remains to be seen; here is an excellent piece on these developments. Let us not miss the irony of this, in view of the fact that it is immigration that is saving Italy from a precipitous decline in population!

As things around the world get worse, more people are talking about becoming migrants. This is how it has always been. I think of my own ancestors abandoning their homes in Europe for the promise of a better life in America, Vilhelm Moberg-style. The irony is that now, the flow may be reversed, with more and more people noticing that the quality of life is actually better east of the Atlantic.

But how will that go?

Future

I am no more able to see the future than anyone else, and much less than some. But I can conjecture. Right now, everything appears to turn on whether Trump will crash and burn or whether he will be successful in his campaign to dismantle the United States as we know it and change the global order.

It is a fact that Trump is already causing changes around the world. Beyond the despicable withdrawal of aid that had been keeping thousands and thousands alive in the Global South,5 there is the heinous treatment of immigrants in the USA that we have already mentioned. He has aggravated relations with NATO, with Ukraine, and with many other once-friendly nations.

But worst of all, Trump seems to be so enamored of Putin that he actually entertains dreams of emulating him: President Trump has repeatedly suggested that he would like to annex Canada, apparently in much the same way that Putin is trying to annex Ukraine.6 He also appears to be serious about invading Greenland, which would, in practice, mean declaring war on Denmark, a NATO member state.7 Think about this: We are talking about the United States going to war with NATO.

How does this affect you? Well, beside the risk of bombs falling and your loved ones being drafted, if you are thinking of emigrating from the US to another country, you have to consider the unfortunate possibility that that country may not accept you. As Trump increasingly erodes relations with nations around the globe, these nations may rethink their willingness to accept Americans as immigrants, and even as tourists. (There is already a new European—that is, Schengen Area—visa program for Americans supposedly going into effect in 2026.8)

Remember that, within certain parameters, each nation is free to decide who it wishes to admit. If the United States closes its borders to citizens of other countries, other countries might reciprocate.

Therefore, if one day you are granted permission to immigrate to another country, be grateful for the opportunity. Americans have long had the sense that everything is open to them, either because they come from The Greatest Nation on Earth or because they have Shitloads of Money. But just ask Elon Musk about Wisconsin—money cannot always buy everything.9

So one question is whether you will be allowed into another country. Another is how you can expect to be received. Here, there are various possibilities.

What kind of reception awaits?

I think that it is important for Americans considering immigrating to another country to understand that they will not necessarily be welcomed by the population of that country. As I see it, there are five main types of reactions to an influx of foreign immigrants. Allow me to caricature them a bit:

“They’re taking our money/jobs/daughters/cats!”

“They’re a threat to our culture!”

“We can totally make some money off of these suckers!”

“Isn’t diversity nice!”

“Whatever.”

All of these reactions are likely to be present in any given context, but the proportions will vary. We have already seen how the MAGA movement has been mobilized through the first of these messages. In many European countries, it is the first two that are the twin workhorses pulling the reactionary plow. But the others will always be present as well.

Let me use Portugal, where I live, as an example. During the past decade, a large number of relatively wealthy foreigners have moved to the country. In part, this was by design: the Portuguese government decided to offer the Golden Visa and the Non-Habitual Resident programs (now partially canceled) as a way of attracting foreigners who could infuse the economy with capital. But how do the residents of the country feel about these programs? They find them to be terribly unfair and believe that they are actually harming the country.

“They’re taking our houses!” might be the Portuguese version of the first reaction above. The influx of foreigners flush with cash and with little understanding of what prices in Portugal should look like have caused housing prices to skyrocket (rising more than 100% over 8 years), due to unscrupulous landlords who want to “make some money off of these suckers”. As a result, suddenly a Portuguese person with an average salary can no longer afford to live in the center of Lisbon or Porto; the Portuguese are being flushed out and replaced with Americans, French, Brits, Germans, Russians, etc. Given this reality, doesn’t it make sense for there to be resentment against this new crop of immigrants?

A related issue that is less obvious but triggers both of the first two reactions above is the parallel cultures that are developing in the large cities of Portugal, and the parallel economies that are emerging. In response to the arrival of the wealthy expats and the digital nomads, new businesses have been springing up where traditional businesses have closed: high-priced restaurants, fancy hipster cafés, brunch places, twee dessert boutiques, artisanal bakeries, yoga cafés (yes), etc. These establishments have two things in common: They reflect cultural practices that are not native to Portugal, and they are too expensive for most Portuguese to frequent.

The result is that you can walk down a street in central Lisbon and see two cafés nearly side-by-side: one, a traditional pastelaria or snack-bar, and the other a gourmet hipster café. A coffee will cost about €0.75 in the first and €1.50 in the second. The first establishment will be filled with about 90% Portuguese people, and the second with about 90% foreigners. To those who argue that the economy is still benefitting from all of these businesses, I would say this: the fancy new establishments are mostly owned by foreigners (and frequently staffed by people who don’t even speak Portuguese), and many of these owners get significant tax breaks thanks to their special status. So in fact, what we are witnessing is the development of a parallel economy in which the non-Portuguese are paying other non-Portuguese for non-Portuguese goods and services.

Again, given this reality, doesn’t it make sense that there is growing resentment?

To end on a slightly more positive note, there will always be people in the fourth category above, who are very happy to see diversity flourish and are pleased to meet people from other backgrounds. I have been fortunate enough to make friends with people from various countries here (including many Portuguese), who see my Americanness, my Swedishness, and my general strangeness as a charming asset, or at least an amusing novelty. But I still do my best to assimilate.

And of course, there will always be those in the final category, who honestly just don’t care one way or another. I would love to say that this group is innocuous, but I suspect that these are actually the people who are deciding elections these days. So maybe we should quietly try to win them over.

This brings us to the end of part 1 of The Good Migrant. In part 2, I will offer potential migrants some best practices and suggestions for eliciting as positive a reception as possible in their new homeland. That will be published next week, so for now… don’t go anywhere.

The previous series, The USA as a Foreign Country, included the essays “Being a Stranger Back Home” and “Why America Is No Longer Home”. Best enjoyed with a stiff drink in hand.

Here are a few sources on classification and terminology regarding migration:

Fantastic post. Although there are also economic reasons, I am primarily considering myself a political refugee. I read the mass psychology of fascism when I was 15 years old in 1975, and I saw America writ large in its pages. The only surprise has been how long it has taken to take affect.

I’m now in the process of packing up my life and getting ready to sell my house and move to northern Portugal.

Although I am generally OK with languages, I find Portuguese to be quite intimidating, but I am intent on learning it. Maybe most of that won’t happen until I get there. But I am intent on integrating, and clearly that is the first and most important towards integration.

Of course that doesn’t mean I will become Portuguese. For better and for worse, I am made in America. But I want to have Portuguese friends, I want to work with Portuguese artists, musicians, choreographers, etc.

And I don’t intend on living in an expensive city in an expat enclave. The idea of living in some condo in the Algarve, or in some Bougie loft in Porto nauseates me.

I live on 6 acres in the country now in the mid Hudson Valley of New York State, and I want to live in the country there, hopefully a bike ride away from the nearest town.

And although I am 65 years old, and doubtless set in my ways, and doubtless will have many challenges, there is also the adventure of trying toadapt! That seems very challenging, but also way more interesting than creating an ersatz American potemkin village to live in, where one is divorced from the realities of the local people that one treats as servants. Ugh.

There is a broken hearted quality to leaving my broken country, but there is also hope that I will find compatriots in my new land, people with open hearts and interesting minds.

This was a fantastic post. I will upgrade to paid ss soon as I feel, I can afford it, in other words as soon as I get over there, to somewhere near Braga.

In the meantime, I am intermittently studying Portuguese and a rather lackadaisical style. I’m going to have to update my game.

I hope to meet you there someday.

Be well.

Your POV on the types of migrants contains nuance as it applies to Europe and comes across less so when addressing America. Taken in whole there is merit in this discussion.

Your description of Portugal resonates with me regarding the influence on the local economy, based on having been a temporary expat in India 20 years ago. The experience living in India helped me comprehend my father and mother’s emotions when my family emigrated from Denmark to America. I was six, not old enough to appreciate anything but excitement.

It is complex to describe all the flavors of loyalty we experience when talking to people who have not lived as a migrant. The clearest description, I think, comes in the saying among some Danish people who live or once lived in America. It is said that a Dane is only happy in the middle of the Atlantic because it means he is either going to America or going back to Denmark.

Keep writing. This is a fascinating topic.