I want to invite you to come with me for a walk in my secret place in Lisbon. It is a universe of contrasts: huge but hidden, rural but urban, wild but controlled, ancient but modern, inhabited but empty. Few people seem to know about it, though it is right in the city, within walking distance of my house. It is called the Tapada da Ajuda.

Technically called the Campus Universitário da Tapada da Ajuda, this huge area sandwiched between the neighborhoods of Ajuda and Alcântara and the Monsanto park belongs to the Instituto Superior de Agronomia, or the School of Agriculture of the University of Lisbon. It was originally called the Tapada Real de Alcântara, thus declared by king João IV in 1645. It has been a semi-private paradise ever since.

The 100 hectares of the Tapada are encircled by high walls, and there are only a few entrances, each with a guard. This fact put me off attempting to visit it for several months, until one day I screwed up the courage to ask—only to learn that the campus is open to the public, and anyone who wishes may go in on foot. Since I learned this, I have made a regular habit of walking there. I would like to take you for a walk there now, complete with many images taken over the past three months. Do you have some comfortable shoes? All right, then. Let’s structure our tour around four fundamental ideas: place, purpose, nature, and time.

Place

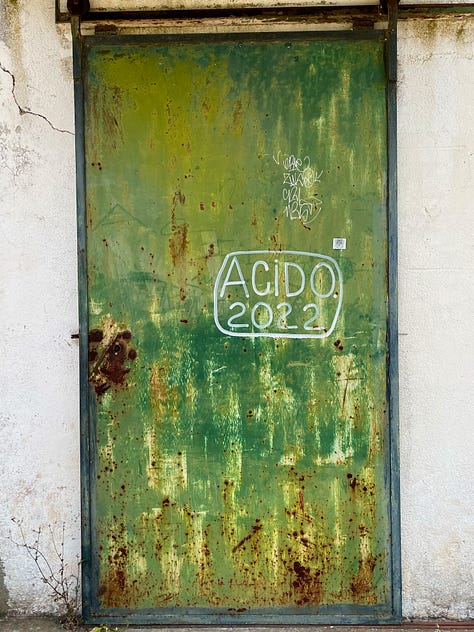

The Tapada (the word itself refers to a walled-in park, and the example given in the dictionary is in fact the Tapada da Ajuda) is a natural oasis right in the city of Lisbon. Nobody I know ever mentions it; I don’t think it is much on the radar of either residents or tourists, since it is considered a university campus. There are five entrances—the word used is portão, cognate with portal, which gives just the right feeling—but the one closest to my house in Ajuda is permanently sealed. The door is bolted, rusted, and covered with cobwebs, and weeds grow around it. So I walk up the hill, past the rooster-topped tower that is the symbol of Ajuda (see above), to the portão between the School of Architecture and the School of Veterinary Medicine (you can tell at a glance which students belong to which school). Many people use this entrance, as there is a fancy school for children inside the walls. But I walk quickly past the school and into the park.

The Tapada is a secret place with secret places within it. There are points where it is impossible to see any traces of the metropolis that surrounds it, although one can always hear the distant rumble of the city, the bridge, and the airplanes that pass overhead every few minutes.

There is a network of roads, paths, and trails extending like the veins of a leaf throughout the Tapada. Titillatingly, some of these are marked as off limits to estranhos, meaning strangers—but it could also mean strange people, so I see the restriction as applying doubly to me. Does that stop me? Not really.

Especially on days when I know few people are working, I have been known to sneak down some of the forbidden paths into the woods, to see what treasures lie there. There is, for example, a miradouro, or scenic viewpoint, which once provided majestic views over the river, but the trees have grown up around it, and its lovely tiled well is all dried up.

Purpose

What is the Tapada for? It is a campus, a botanical garden, a farming laboratory, an urban forest. The many buildings of the School of Agriculture are laid out in graceful patterns, and the land around them is used as a research and practice area for farming and other agricultural techniques. These range from the predictable—olive groves, apple orchards, and vineyards—to the unexpectedly specific—such as the tiny center for patologia apícola, or bee pathology.

In the center of the Tapada is the Real Observatório Astronómico de Lisboa, an observatory completed in 1867. Its immediate purpose was to settle a raging international dispute among astronomers about the parallax of stars. However, the Portuguese being a proud people, they stated their aim as “promoting Sidereal Astronomy, discovery and understanding of the infinite cosmos, and concern about the exact mapping of the sky and measuring the size of the universe.”1 Now that is a goal. I have not yet been able to visit the observatory, so I have contented myself with gazing at it from without, a terrestrial observation of no great import.

Being a part of the University, the Tapada is used for more than just research; it houses a giant rugby field (the School of Agronomy has a team), and there is a restaurant that is open on occasion.

From my perspective, however, the Tapada is a place for taking long walks. In fact, I sometimes go there to plan one of my essays; the total solitude I can achieve walking along the roads and the paths here allows for excellent “thinking walks”, in which I develop my ideas out loud.

Nature

One of the fascinating things about the Tapada is the many different micro-environments that it contains. There are rows of olive trees tagged with their genetic information; there are vineyards labeled by grape variety; there are woods filled with oaks, pines, eucalyptus, cork trees and the wild olive trees known as zambujeiros.

There is also a large pond where frogs exuberantly emit their electric squeaks. And then there is the Terra Grande, the giant field covered with cereals where the swallows sweep and chitter as they gobble insects.

I love to wander through the Tapada, admiring the flowers and greeting the birds. I have seen blackbirds, falcons, crows, warblers, goldfinches, peacocks, the occasional flock of bright-green parakeets, and once, a red-legged partridge—imagine, a partridge in the middle of Lisbon! Recently, I watched a remarkable scene right outside the main building of the Instituto: a jay was trying to catch a lizard, which was in turn trying not to be caught. The jay’s wild squawking and flapping made for quite a spectacle, but the lizard was too fast for it and made it into the safety of a drainpipe.

The flora of the Tapada is a feast for the senses. Lisbon has a climate that is welcoming to species of plants from all over the world, and the Tapada is filled with roses, prickly pears, morning glories, loquats, pomegranates, and hundreds of other kinds of trees and flowers. These greet me like supporters along the route of a marathon as I make my rounds.

But of course the special genius of the Tapada is how it showcases the symbiosis of nature and humankind. The production of olives, grapes and cereals is testament to the ancient European tradition of squeezing the very best from nature. It is heartwarming to me to watch these traditions being passed down from one generation to another, and even improved in the process, which brings us to our final topic: time.

Time

Time is everywhere in the Tapada, if you look for it. On a small scale, I have watched the changes in the plants as spring has faded into summer. This helps me to feel more mindful of the moment, and more grounded in this place.

But time is present on a larger scale, as well. Wandering around the Tapada, I encounter tractors and wagons built and used by previous generations. I find decrepit buildings that were once proud loci of education or royalty. The old rots away very slowly as the new begins to blossom.

There is, I feel, a deep connection between Portugal and decay. The national notion of saudade—a melancholic longing for something lost or unattainable—is incarnated in the crumbling walls, broken windows, and even graffiti that fills much of Lisbon, and the Tapada is no exception.

There are several emotional waves that I surf here. There is the recognition of the beauty that can be found in decay—my beloved concept of non-canonical beauty—which gives me an aesthetic thrill.

But there is also the sense that progress is sometimes a red herring, a herring pursued so frenetically by those in the North. Having come here from a more modern part of Europe, I am learning to make peace with the idea that not everything must change at all times. There are places here in Lisbon that seem timeless to me; they could be from any decade from the Forties to today. And this perception instills in me a sense of peace, a quieting of the hurry with which I was raised. The Laboratório Professor Pais de Azevedo seems to exist in a time before I was born. The lichen on the walls and the roses outside create the impression of a tomb. A laboratory-tomb—what could better represent a rupture with the normal course of time?

Of course, there is also the magnificent architecture of the main building of the Institute, and the steel-and-glass Pavilion of Expositions built in 1884. These illustrate the proud ambition and the patient attention to detail of a time that is lost to us.

And yet, and yet: The future is present, as well. The campus is populated by the agronomists of tomorrow. They are young and vigorous and laugh and drink beer, like students virtually everywhere. I remember seeing a knot of students walking up the slope toward the main building, one girl gripping the backpack of a boy, cleverly harnessing his labor and enjoying an easier ascent.

These people are developing the means for us to survive in a future made uncertain by changing climates. The vineyard in front of the main building boasts an experiment in “agrivoltaics”, in which solar panels placed inside vineyards both harvest solar energy and protect the vines from excessive sun and rain. These students are the people who will guarantee that we have wine in our old age.

To travel through the Tapada is to travel through both space and time. By the time I emerge on the other side, a few kilometers after entering, I feel that I have visited many worlds. I emerge into the neighboring neighborhood of my neighborhood, Alcântara, with my senses heightened to its beauty, and ready to sit with an espresso and write down the ideas that I have incubated during my trip. Today has been another good walk. I hope you have enjoyed it too.

If you enjoyed this essay, you may also enjoy the following pieces:

This is the translation found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisbon_Astronomical_Observatory.

Wow, I am trying to write something clever but just want to say what a lovely walk! It felt magical and very portuguese. This mix of decay and grandeur can be found in Coimbra as well. With its old university, the library, prison dungeon and then the old train station. A city very much worth visiting.

To quote an old American TV show: I want to go to there. (And maybe I soon will?)