Re-using and reliving

Many years ago, when I was living and working in Boston, I had a Venezuelan friend, who told me that the two things that surprised her most about the US were that everybody she knew had tried marijuana (not me, Mom, I swear!), and that people would buy and wear used clothing. She said, “In Venezuela, nobody would think of wearing clothing that someone else had worn.” I found that fascinating; given the lower income levels in Venezuela, it might make sense that people would economize by recycling things like clothing—but apparently they don’t. However, I never asked her why that was.

Meanwhile, in Stockholm, where I lived more recently, there are stores that do killer business selling used garments from the United States. Many Swedes apparently love the idea of wearing clothes that someone else has worn, especially if that person was an American. For such clothes, they will pay top dollar. At the same time, Stockholmers who can afford it will rotate their wardrobes with great regularity. I kind of hate to admit it, but I briefly dated a woman living in Östermalm (the fancy part of Stockholm) who told me that she had girlfriends who boasted that they never wore the same dress twice.

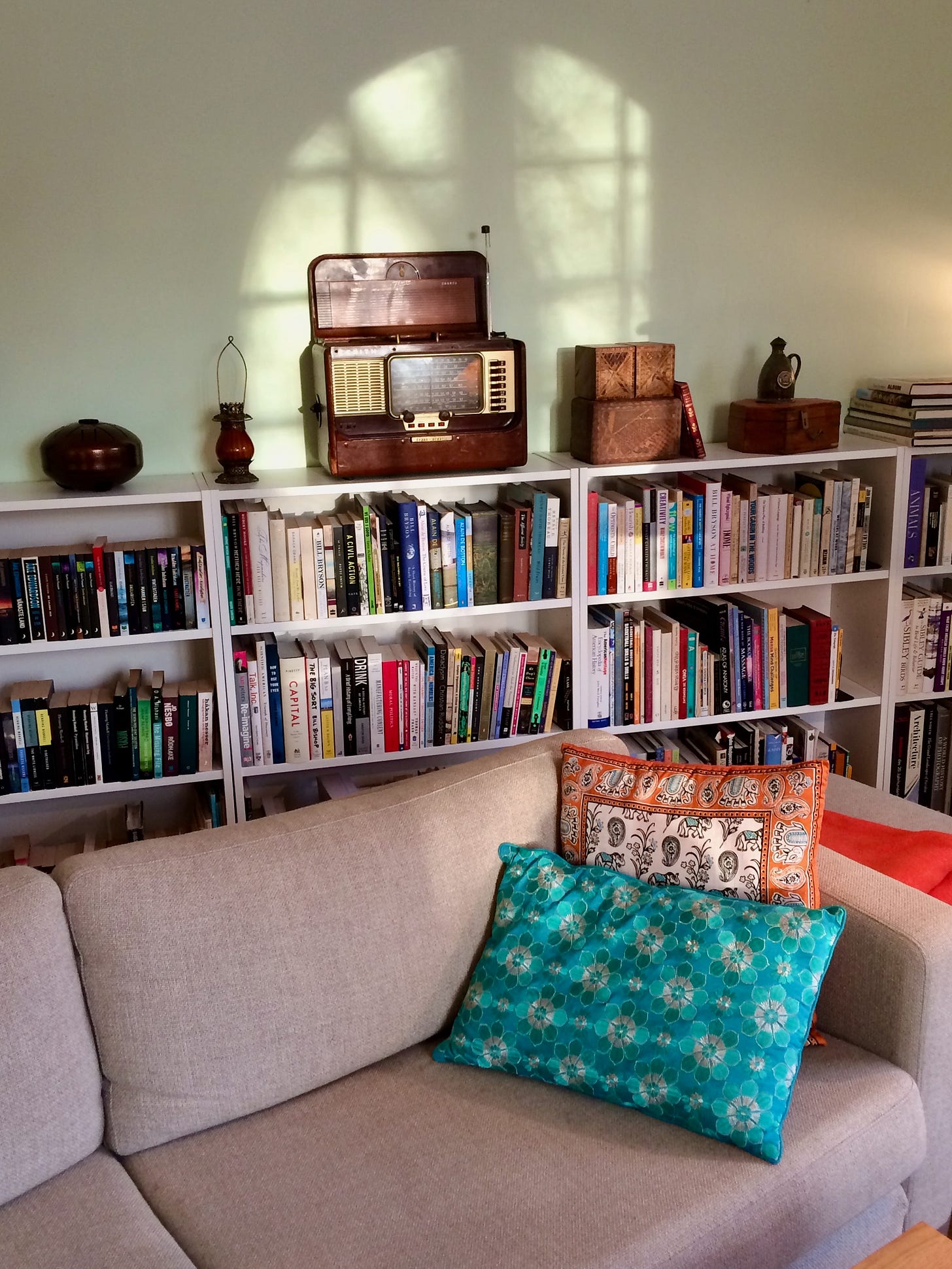

Right now I am thinking a lot about stuff—specifically, about material possessions. I am in the middle of a move from one apartment to another here in Lisbon, and—as happens when we move—am being forced to confront not only the things that I have chosen to acquire, but also the things I have chosen to keep. Marie Kondo, about whom I will have more to say shortly, points out that “our possessions very accurately relate the history of the decisions we have made in life.” For this reason, every time we move house, we are forced to relive, or at least re-encounter, our own personal history.

Our relationship to stuff

I am someone who has a complicated relationship with stuff. I have always owned far more things than was good for me. I remember when my ex-wife and I made our big trans-Atlantic move from the US to Sweden, and (after being given a very misleading quote for shipping) sent an entire container filled with furniture, books, clothing, kitchen implements, papers, memorabilia, and things that, years later, I looked at and said, “Why on earth did we keep this?” I have many possessions that have cost me far more to ship around than to acquire. And I’m not even sure I really want them.

Having pondered my complicated relationship with stuff for many years, I have come to believe that our behaviors around acquiring and disposing of possessions are affected in interesting ways by both cultural factors and individual factors. I would suggest that, if we want to understand a person’s relationship to stuff, all of the following factors are all of potential importance:

wealth

materialism

capitalism

fear/trauma

conscientiousness

sentimentality

other personality factors

Let me explain these a bit. Obviously, the amount of disposable income anyone has will affect their patterns of acquisition, as will the degree of materialism of the society or family they have grown up with. I come from the United States, which is a materialistic country par excellence; but in addition, I come from a stuff-loving family. Branches of my family have been in North America for over 300 years, and many finely crafted items have been passed down as heirlooms. (Sometimes I think we call it an “heirloom” because the air gets heavier as it looms over you. But I digress.) My mother, bless her, has put together a wonderful collection of beautiful items that go so far beyond covering her needs that the last time my parents moved, one truck was not enough.

This brings back a memory: One wonderful Thanksgiving, about the same time I discussed used clothing with my Venezuelan friend, I took my girlfriend and another couple down to visit my parents where they were living in Pennsylvania. One of my friends, who had grown up in Kansas City, was awestruck by the ambience of my parents’ house, and said, “I’ve always dreamt of houses like this, with a sense of history. In Kansas City, we always had just the things we needed—nothing fancy, and everything more or less new, probably bought at Sears.”

As you might imagine, I have inherited from my mother quite a number of heirlooms, but also her penchant for acquiring things. The problem is that this tendency does not go at all well with an itinerant lifestyle. As I have moved from country to country, I have schlepped with me far more things than I really needed. Plus, most of the countries I have lived in had Amazon.

I list capitalism as a factor, because to some degree, we are surrounded by systems designed to facilitate and promote the acquisition of stuff. Amazon is probably the best example, though anyone who uses social media will also know what I mean. It has never been so easy to shop for things and as a result, end up with more than we need.

But let’s move from the environmental factors to the individual factors that cause us to buy, sell, hoard, or purge. I think that fear—often linked to past trauma—is behind many people’s tendency to amass far more things than seems reasonable to others. My brother once had a roommate who had not always had enough food as a child, and as a young adult, when he cooked for himself, he always prepared at least twice as much food as he could eat. Also, we have all known or heard stories of grandparents who went through the Great Depression and came out with a terrible fear of scarcity, which translated into hoarding behaviors that were incomprehensible to those who had not known deprivation.

For me, conscientiousness is a major contributor to my troubles with possessions. I have many items that I would love to get rid of, if I could just be certain of finding the right person to give them to. Once I own something, I want to use it properly, and once I have used it, I want to dispose of it properly; throwing a book in the trash is completely unthinkable to me. Especially after living in Sweden, I recycle as though it were a religion and I were a druid of plastics. The lack of composting in Lisbon feels downright traumatic. Another challenge, in a new city or a new country, is to learn exactly where to take things we no longer need.

Here is an example: We used to have something called “the dump”, which was where we took things and, well, dumped them. Then with the advent of recycling, there were also naming reforms. In Stockholm, we had a place called the Återvinningscentral, or “Recycling Center”. In the US, my parents now take their refuse to a place called the “Transfer Station”. Here in Lisbon, it took me ages to find the place where I could take my old cardboard boxes and bundles of plastic wrap, in part because it is called the Parque de Apoio à Remoção, literally “Park of Support of the Removal”. But of course—why didn’t I think of that?

My other big hangup is sentimentality. Who among us does not hold onto things that were given to us just because they were gifts? Or hang on to keepsakes and mementos because of the experiences they remind us of? But honestly, I am a major offender. I have hundreds of such things that I dutifully ship from place to place as I move: stones from beaches I have loved, old concert ticket stubs, love letters, seashells, drawings by children, photographs I used to display, and so on. If college students could major in nostalgia, I would be teaching the senior seminar (and would probably annoy them with stories of courses of yore).

To end my list of factors that affect our dealings with stuff, I found that I needed one catch-all category, for “other personality factors”, because people can show surprising complexity. For example, I have a friend who used to keep all of his empty shaving cream cans, for reasons that even he was unable to explain. In my case, I have stores of raw materials—bits of wood, string, foam rubber, cork, etc.—that, in fits of hallucinatory optimism, I dream of using in all manor of creative and practical projects: artworks, bulletin boards, portable desks, phone holders, a playground for my turtle, and so on. Clearly, amassing stuff can be motivated by optimism as well as by fear.

Enter the Kondominium

About a decade ago, I read, as did nearly everyone else, Marie Kondo’s book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. For a while, everyone was fascinated by the ideas presented in this book. Then the tide turned, and it seems to me that we are now in an anti-Kondo moment. (I recently read a review of a book proclaiming the glories of Maximalism.) But whatever people currently think about Marie Kondo, her book had a profound effect on my thinking about stuff.

Take, for example, these surprisingly insightful statements:

The question of what you want to own is actually the question of how you want to live your life.

We should be choosing what we want to keep, not what we want to get rid of.

[W]hen we really delve into the reasons for why we can’t let something go, there are only two: an attachment to the past or a fear for the future.

I remember sitting in my apartment in Stockholm, surrounded by books I felt I should read and papers I was not sure I needed to keep, and reading that ”[l]etting go is more important than adding,” which felt liberating.

Perhaps more than anything else, Kondo spoke sternly to the sentimental side of me, offering a better way to think about gifts and mementos:

Presents are not “things” but a means for conveying someone’s feelings.

It is not our memories but the person we have become because of those past experiences that we should treasure. This is the lesson these keepsakes teach us when we sort them. The space in which we live should be for the person we are becoming now, not for the person we were in the past.

So did reading Marie Kondo change my life? Um, no. Not really. I was never able to do the full-scale purge that she claims to be the one true path to minimalistic Nirvana. But it did help me learn to let things go in a graceful manner. For example, when I was preparing to leave Sweden two years ago, I got rid of about half of my possessions, which felt like a major achievement.

So where does it all go?

But that brings us to the twin questions that so many of us struggle with: What do do with things, and when.

Ideas about storage are something that seem to vary culturally. In a past incarnation, I was actually someone who owned a barn in Sweden. (Just to be clear, not a barn, which in Swedish would be a “child”. That is frowned upon.) And as a neighboring farmer said sagely with a nod, “A barn has a tendency to fill up.” In other words, our space, much like our time, tends to fill up until we become unhappy with the result.

Interestingly, the amount of space that any given household has available seems to vary quite a bit between countries, even if we stick just to urban or suburban settings. I remember calling a friend once from my cramped little apartment in Uppsala—an American who lives in the Midwest—and asking her how big her house was. She said, “Oh, boy, let’s see... I would have to count the rooms.”

In Sweden—a country with smaller homes and hugely distinct seasons—it is normal for a rental apartment to come with a storage area in the basement (or possibly the attic), where one can put bicycles, sleds, winter tires, beach chairs, camping equipment, old appliances, piles of magazines, or whatever one doesn’t want to have in the apartment proper at the moment. I became very accustomed to making use of such space while living in Sweden.

Then I moved to Portugal, where no rental apartment that I have seen comes with any storage space outside the apartment itself. The reasons for this are pretty clear: Portugal is a much poorer country, and the cellar areas that, in Stockholm, would be used for storage are, in Lisbon, inhabited apartments complete with a back courtyard. There is never a bicycle room—something that is quite standard in Sweden. Nor, sadly, is there a room for the garbage/recycling bins, which often end up in the main foyer of the building. When people here become desperate for storage, they glass in their balcony and then fill it will all of those things that they aren’t currently using.

But also, people just learn to get rid of things. In Portugal, there is a very robust tradition of buying and selling used goods, with copious second-hand shops and flea markets such as the famous Feira da Ladra in Lisbon, which attracts so many tourists that the prices have started to skyrocket. And, with Portugal being a less wealthy and less materialistic country than the United States, people seem to content themselves with far fewer possessions.

One of my happiest stuff-moments in more materialistic Sweden was when I learned about a new company called Sellpy. The Swedes, being excellent in both innovation and technology (if not in snuggling), have come up with a number of solutions to the age-old problem of how to get rid of things. This problem has become more and more acute in Sweden as disposable income has increased and American-style patterns of consumerism have taken over. Here is how Sellpy works:

You create an account online and order some bags.

A number of rugged suitcase-sized plastic bags are mailed to you.

You fill these bags with whatever you want to get rid of, short of actual garbage.

You put these bags on your doorstep, and alert the company that you want them picked up.

They send a person to retrieve your bags.

They sort the items into sellable, charity, or trash.

Anything they think they can sell, they photograph and put in their online shop.

If they sell anything, they split the profits with you.

There are more nuances, but you can read about them on their website if you’re interested. The point that I would like to highlight is that the vast majority of the work is done by the company, not by the client. It is amazingly easy to fold up some clothes and stick them in a blue bag together with whatever equipment or decorations one is tired of owning.

This is just one example of many systems of stuff-removal out there that appeal to individuals like me, who find themselves frozen by conscientiousness, cluelessness, or simple lack of initiative.

The problem? Even with these wonderful-seeming systems, there is no guarantee that our ex-possessions will not go into a landfill, or help to destroy local industries in the Global South. In West African countries such as Ghana, for example, there is the phenomenon of “Dead White Man’s Clothes”, in which garments discarded by Europeans are sold (not donated, mind you—sold) to wholesale merchants who ship them to African countries, where they are sold to local merchants, who then sell them to customers. The customers buy these clothes partly because they see them as of high quality or status, but mostly because they are cheap. And that essentially ruins business for both companies and individuals producing clothing in Africa, who simply can’t compete with the price of cast-off clothing.

So really, one’s conscience gets no respite. Maybe it really is just better to own fewer things after all.

Speaking of dead people

The other day I found myself having lunch in Lisbon with a Venezuelan. And suddenly a thought struck me, and I dug a half-buried conversation out of the landfill of memory. I said to him, “On another topic, do people in Venezuela every buy used clothes?” He laughed and said, “No way!” When I asked him why he thought that was, he said, “What if the person died?” He said that in his understanding, people had a superstitious belief that it would bring bad luck to wear the clothes of a dead person.

You certainly can’t say that culture doesn’t affect our relationship to stuff. After all those years, it felt good to get a bit more perspective on my friend’s comments. I wish I could say that at this point, we were passing around a joint, but in fact we were in Starbucks having a latte. Sigh. Long live capitalism!

Interesting. I gave almost everything away when I left the U.S. for Sweden. It wasn't difficult because I was desperate to leave and in a big hurry. But sometimes I see my old things in photos and I miss them. All that stuff bore witness to time, for me. I had the stuff, so I didn't have to do the work of making sense of what it all meant. Possessions are kind of a way of stopping time.

Great post—a marvel of clearing out various related thoughts that might otherwise gather dust in the attic of one’s mind. But I’m surprised that you didn’t cover one topic that has been a source of mild obsession for Bina (my wife, your friend): Swedish death cleaning. See the link below for one of many online articles about it. Here’s the money quote: “‘Some people can’t wrap their heads around death. And these people leave a mess after them. Did they think they were immortal?’ ... The benefit of death cleaning to your loved ones who won’t have to do it for you is fairly straightforward.” In other words, not just the sins of the fathers, but also their stuff, is visited upon the children, and we should relieve our heirs of this burden if at all possible.

LINK: https://www.nbcnews.com/better/health/what-swedish-death-cleaning-should-you-be-doing-it-ncna816511